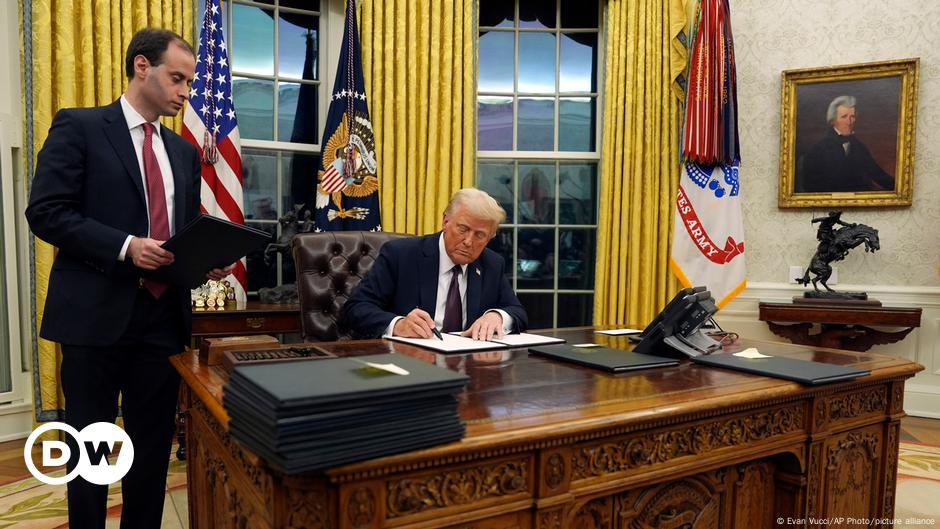

- Donald Trump has signed an executive order to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization.

- The US is the largest financial contributor to the WHO, mostly through voluntary payments to its preferred programs.

- Experts express concern about the US’ ability to address global health issues alone.

Donald Trump has pulled the United States out of the WHO , amid a slew of executive orders on the first day of his presidency.

Experts warn the move will severely impact the ability of both parties to address disease outbreaks and other global health concerns.

A long-standing congressional resolution requiring the president give a year’s notice and pay back any outstanding obligations means the order won’t take full effect until January 2026.

In his order, Trump instructed the US to “pause the future transfer of any United States Government funds, support, or resources to the WHO”.

The US is the biggest source of WHO funding

US withdrawal from the WHO is a major blow to the organization’s budget and its ability to coordinate international health programs and policy.

The WHO is a United Nations agency currently comprised of 196 member countries, which pay into the organization via “assessed contributions” — effectively a membership fee — based on GDP and population figures on a two-year funding cycle.

The US accounts for nearly a quarter of these funds, ahead of China, Japan and Germany.

Nations can also make voluntary contributions, which the US does. In the current cycle, the US has already contributed almost $1 billion to the WHO budget.

About half of the WHO’s funding comes from non-governmental organizations. For example, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation donates hundreds of millions, making it the second-biggest contributor overall.

Donor-directed or “specified” contributions — where the giver dictates how and where the money is used — account for more than 70% of the total budget.

That presents a deep structural problem for the operation of the WHO, according to Gian Luca Burci, a former WHO lawyer now working as a global health law specialist at the Geneva Graduate Institute.

“Donors attach a lot of strings, so the WHO becomes very donor-driven,” Burci told DW. “The US gets quite a bit in terms of return for relatively little money.”

“There are many issues that the US attaches a lot of importance to, regardless of who sits in the White House,” Burci added, “in particular on health emergencies, on pandemics, on disease outbreaks, but also on getting data of what happens inside [other] countries.”

The loss of its top financial contributor leaves the WHO with few options to make up the shortfall. Either other member states will need to increase their funding, or the WHO’s budget will need to be stripped back.

Leaving the WHO would also hurt the US

The relationship between the WHO and Donald Trump began to deteriorate in 2020, when he accused the WHO of being a “puppet of China” during its response to COVID-19.

Upon signing his executive order, Trump again criticized China’s “low contributions,” saying “World Health ripped us off”. While China is the second biggest contributor in terms of assessed payments, its voluntary contributions are just $28 million this cycle, compared to $697.9 million from the US.

“He continues to rail against China and says that WHO is in the pocket of China, that China influences it,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law and director of the WHO Collaborating Center on Public Health Law and Human Rights at Georgetown University, US.

Gostin said exiting the WHO would be an “own goal” for the US and would come at the cost of the “enormous influence” the country has in global health.

“I think it would be deeply adverse to US national security interests. It would open the door to the Russian Federation, China and others. That might also be true with the BRICS: South Africa, India, Mexico,” Gostin told DW.

Can “America First” protect itself from global health challenges?

Trump has ordered his government to identify “credible and transparent United States and international partners to assume necessary activities previously undertaken by the WHO.”

At the same time, the new administration is likely to wind down a Biden-era Global Health Security Strategy intended to monitor and protect against infectious disease threats.

“There are many things the United States can do alone, but preventing novel pathogens from crossing our borders simply is not one of them,” Gostin said.

He points to the current concerns around H5N1 avian influenza in the US: “We’re not going to have access to the scientific information that we need to be able to fight this because avian influenza is a globally circulating pathogen.”

Will the WHO have to make do without US money?Image: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP

Will the WHO have to make do without US money?Image: Fabrice Coffrini/AFP

Threat could force more change, and US win

Trump’s withdrawing the US from the WHO transforms the US-WHO relationship — for now.

Burci is open-minded about what a future relationship could look like, suggesting the US could selectively fund WHO programs it has ideological alignment with.

Trump also casts himself as a dealmaker president and could use the withdrawal as a stick to force US-endorsed reforms in Geneva.

The WHO’s performance has long been criticized, and not just by the US. However Gostin notes some reforms have begun in the wake of its handling of COVID-19.

While WHO’s “transformation agenda” has also been in place for nearly eight years, Trump may be able to further strong-arm change.

Gostin would rather see Trump engage his dealmaker than isolationist persona in his WHO dealings.

“He could do a deal with WHO to make it a better, more resilient, more accountable and transparent organization, which would be a win-win for the United States, for WHO and the world,” Gostin said.

Edited by: Fred Schwaller

This article was updated following Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the WHO on Jan 20, 2025.