What happened when Trump officials accidentally texted him their war plans

Illustration by The Atlantic

March 24, 2025, 9:50 PM ET

Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube | Overcast | Pocket Casts

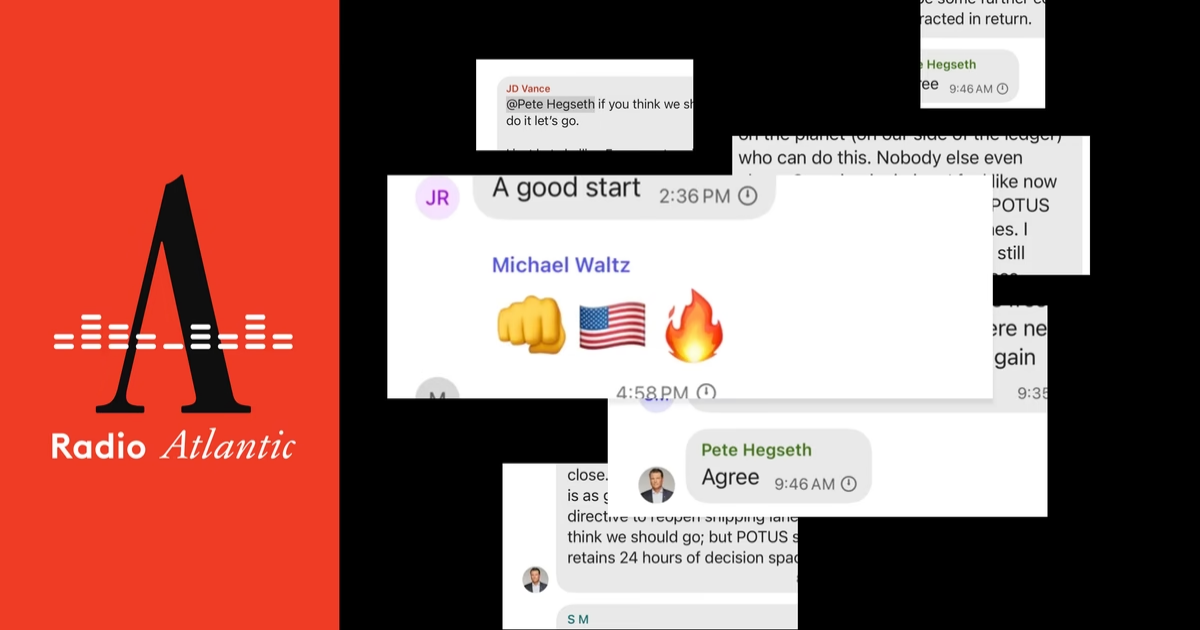

It’s happened to the best of us. We mistakenly send a text about a colleague we are mad at to that very colleague. We accidentally include our mom on the sibling text chain about our mom. Today on Radio Atlantic, a much higher-stakes texting error: The Atlantic’s editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, received a connection request on Signal from a “Michael Waltz,” which is the name of President Donald Trump’s national security adviser. Two days later, he was added to a group text with top administration officials created for the purpose of coordinating high-level national-security conversations about the Houthis in Yemen. On March 15, Goldberg sat in his car in a grocery-store parking lot waiting to see if the strike would actually happen. The bombs fell. The text thread had to be real.

We talk with Goldberg about this absurd chain of events, and with Shane Harris, who covers national security for The Atlantic, about what it means that defense officials were discussing detailed war plans on a text chain.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Hanna Rosin: On March 15, the U.S. began a bombing campaign against Houthi groups in Yemen. A couple of hours before that, our editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg, sat in his car in a supermarket parking lot, waiting to see if and when the attack would start. How he knew about this military campaign is a very weird story. Not long ago, Jeff was added to a text chain of very important people in the administration. Presumably, he was added to it by accident.

I know, it happens to the best of us—but there was the editor of The Atlantic monitoring the back-and-forth between Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, Vice President J. D. Vance, and others, wondering: Could this possibly be real? In fact, Brian Hughes, the spokesman for the National Security Council, later confirmed that it was indeed all real. I’m Hanna Rosin. This is Radio Atlantic, and today, we have on the show editor in chief Jeffrey Goldberg and staff writer Shane Harris, who covers national security, to explain what happened and what it might mean.

Jeff, welcome to the show.

Jeffrey Goldberg: Hey, Hanna.

Rosin: Hi, Shane.

Shane Harris: Hi.

Rosin: Jeff, on Tuesday, March 11, you get a Signal message from a user identified as Michael Waltz, which is also the name of President Trump’s national security adviser. Where are you when you get this message, and what are you thinking?

Goldberg: Weirdly and randomly, I was in Salzburg, Austria, and what I’m thinking is not much, because in my line of work, that wouldn’t be the craziest thing to happen.

Rosin: Like, it could be him; it could be someone pretending to be him. You’re not that fussed.

Goldberg: Well, I am always cautious about people reaching out across social media or messaging apps.

I don’t assume that they’re the person that the name suggests, but I would have to say that I was glad, also, and I was hoping that it was the actual Michael Waltz, because I’d like to be in regular contact with Michael Waltz for all the obvious journalistic reasons.

Rosin: Right. So you’re like, Oh, maybe he has a scoop for me.

Goldberg: Yeah.

Rosin: Okay, so then what happens next? You’re going about your life, going about your business, and …

Goldberg: And then I get added to a group, a Signal group—you know, a text-messaging chat group—called “Houthi PC small group.” PC I know from covering White House issues, you know: “Principals Committee,” basically the top leaders of Cabinet departments generally associated with national-security issues, and then a message from Mike Waltz talking about how he’s putting together this PC small group to talk about the Houthis, because something’s gonna be happening over the next 72 hours. That’s when I sort of think—I mean, honestly, the first thing I thought was: I’m really being spoofed. Like, somebody is—this is a hoax. This is a state or nonstate actor, probably nonstate actor, looking to entrap, embarrass, whatever word you wanna use, a journalist.

Rosin: Right. So you’re on alert. Like, it’s a little bit interesting, but also …

Goldberg: Hanna, as you know, I’m always on alert.

Rosin: Yeah, okay, okay, okay.

Goldberg: Hanna, what am I gonna tell you?

Rosin: All right, so then, so maybe it’s a spoof, maybe it’s not. How does it start to get more real?

Goldberg: Well, it gets real in the sense that if somebody’s doing a spoof, it’s a very, very accurate spoof. What happens is, a number of Cabinet-level officials start reporting into this chain, giving the names of their deputies or contact people over the weekend, when, clearly, something’s gonna happen in Yemen. Uh, in retrospect, clearly something’s gonna happen in Yemen. And that was that for that day; it was the next day that they start engaging in a policy discussion really in earnest. And it’s, you know, explicated in the story that I wrote. But, um, that’s when I’m sort of thinking to myself, If this is a simulation or this is a fake, someone’s going to a huge, huge length to make it seem real, because everybody in the chat sounds like the person who they’re quote-unquote playing. So I don’t say I’m 50–50; I’m still 60, 70, you know, 70–30 this is a fakery, because, for the simple reason that this is nuts—I mean, obviously why, why would I be involved in this?

Rosin: I wouldn’t even know what to think, because yeah, like, we include people on text chains who we shouldn’t. Like, the mistake seems as implausible as the reality—like, every version seems implausible.

Goldberg: We all make the mistake. This is why this is so relatable. Yeah. We all … I’m thinking of Shane, and I’m writing to Hanna about Shane—an assignment, or how great Shane is. And I type in Shane into the recipient, because that’s the name that’s on my mind.

I don’t know what was going on in Mike Waltz’s mind, who he was thinking of—we’re trying to figure that out, still trying to figure that out. But in any case, I was added to this group, and it’s a misdirected email or text chain that I shouldn’t have been on. But the larger point—and obviously Shane can speak to this—the larger point is that: Why is this conversation happening out in the open? Now, I know Signal is end-to-end encrypted, but it’s a commercial texting service that anyone, not just people with security clearances in the federal government, can join.

So, so, and that’s the essential danger, and that’s, if you want to think about it, an original sin. The original sin is communicating very sensitive information in a channel where you can mistakenly bring in—I mean, forget the editor of The Atlantic. You could have brought in a Houthi, for all you know. You could bring in somebody who is actively sympathetic to the Houthis and sharing real-time information with you. That’s somewhat appalling.

Rosin: So, Shane, I’m gonna ask you about that in a second, but I need one more part of the story before we move on to that. Give me an example of—you said it sounded like them. Like, if it was a simulation, it was an amazing simulation. Can you give us an example?

Goldberg: Sure: Pete Hegseth writing an all-caps about how he finds the Europeans pathetic. J. D. Vance sounding like a kind of quasi-isolationist, talking about: Why would we do this sort of thing? Europe doesn’t—Europe should take care of this problem; it’s not our problem. Trade conversations. The most interesting one, and the one that I thought, Whoa, that really does sound like the guy: At the end of this chain, Stephen Miller, or I should say “S M,” a person identified as “S M,” comes in and basically shuts the conversation down and said, I heard the president. He was clear to me; he wants to do this. It was basically—and obviously this is really interesting—it’s a conversation with not only the secretaries of state, treasury, and defense, but the vice president of the United States, and here comes Stephen Miller, deputy chief of staff, ostensibly just deputy chief of staff, coming in and saying, Uh, everybody, uh, the president spoke. I heard it. Y’all need to just stop doing what you’re doing. And then everybody kind of gets in line and, like: All right, well I guess we’re attacking Yemen.

Rosin: It’s so crazy that you’re just watching this conversation unfold.

Goldberg: Look, the White House has confirmed that this is an authentic chain, but we’re still trying to figure out some aspects of it. I still don’t know the identities of one or two people, because they had their initials. So when we talk about them, I’m assuming that “S M” is Stephen Miller, but I’m not guaranteeing that to you.

That’s a good example of one person. On the other hand, obviously, the one called “Hegseth” is Hegseth.

Rosin: So you heard Vance disagree with the president, which almost never happens publicly. That’s interesting.

Goldberg: I mean, to be fair to all vice presidents and presidents, it never happens in any administration, where a vice president is gonna go out and, I mean, of course he didn’t go out here. He thought he was—actually, it’s really, it’s interesting, because Vance is saying in the conversation: I don’t think the president understands the ramifications of what he’s doing. He’s saying that to people who work for the president. It’s kind of a bold move, to say: Trump doesn’t understand what’s going on. And now if I’m just sort of—this is just speculation—but if I’m Stephen Miller, and I’m reading that, and I’m the enforcer, I’m like: Okay, thanks, J. D. That’ll be enough of that.

Rosin: Right, right, right, right, right. So some of the things are, like, overheard across the bathroom stall—you don’t hear them in public. Other things are, like, exactly as you expect.

Goldberg: Right, right, right. Other things are exactly as I expect. I mean, even later in the story, when, after the first successful strike on the Houthis in Yemen—

Rosin: And that’s when you know this was real.

Goldberg: Well, then I know it’s real, because I was told beforehand that it was gonna happen, in my phone, and then two hours later it happens.

That’s pretty good proof that, you know, if somebody is spoofing this, then it’s not some media-gadfly organization. It’s a foreign intelligence service that had knowledge of the U.S. strikes—seems implausible. But then the part that really struck me as very Trump administration was the sharing of all these emojis: flag emojis, muscle emojis, fire emojis.

Rosin: Prayer emoji.

Goldberg: Prayer emoji, which, you know, and it’s like, by the way, I mean, it was—talk about relatable. It’s like every workplace—I mean, this is what I actually thought when I’m seeing this come over the phone, is Wow, every workplace is the same. It’s like, Big victory! We got the new, you know, the Dunder Mifflin contract, and, you know, muscle emoji, and it’s like, here was, you know, We took out some Houthis! Good, good, good work, everybody. So that’s when I thought, Wow, these guys are—these could be these guys. Because if I were trying to spoof them, I wouldn’t do something so implausible as to start inserting juvenile emojis into a national-security conversation.

Rosin: Unless you were so good.

Goldberg: Yeah, no, if I had outfoxed myself, you know. I wouldn’t have done that if I were doing a simulation.

Rosin: One more question about your reality: As all this is happening and you’re starting to realize this might be real, are you talking to people about it? Are you in your own reality about it? Are you, like, where are you?

Goldberg: Well, I’m talking to certain colleagues, including and especially Shane, who’s sitting next to me. Shane, who’s been covering the intelligence community for a long while. And, you know, I’m talking to him from the beginning about this, ’cause I do need some reverb, some reaction to it, ’cause it’s never, I’ve never seen this kind of thing or heard of something like this happening.

But when I first showed him just the initial foray—you know, the “we’re having a group”—Shane was like, No, no. Somebody’s trying to—this is an operation. I don’t know who it is, I don’t know why they’re doing it, but this is an op. This is a disinformation operation, because these guys don’t do that.

Rosin: Okay, Shane: “These guys don’t do that.” Why was that your first thought? What don’t they do?

Harris: I mean, what they do is talk about who we’re gonna bomb and why should we bomb them. They don’t do it on Signal. And, I mean, in the initial presentation of this that Jeff gave to me, I thought: Well, this, this sounds crazy. Why would they be that reckless? Why would the national security adviser set up a group, call it, you know, PC Houthi group, and then start adding these people?

And it was actually kind of baffling, too, because, again, if this was a hoax, somebody was going to really great lengths to do it—which could happen.

Goldberg: I mean, you know, sophisticated operations do happen in the intelligence world.

Harris: Then the question was, of course: Why? To what end? So where is this going? And then as it went on, I think it became, like, as Jeff said, increasingly clear that the needle was moving quickly towards authentic. But my initial reaction as to why it was probably not real was: I couldn’t imagine senior national-security officials deciding that it was a good idea to discuss something of this sensitivity where, let’s be clear, pilots are in the air, they could be shot down, people could be killed, people are going to be killed on the ground—things are happening very fast. Why would you not do that in the Situation Room or in a secure facility? Many of these Cabinet officials, by the way, have facilities like that in their house. They can go have those conversations.

Goldberg: Most of the relevant ones, the heads of intelligence agencies, the, obviously, defense secretary and the like, they have plenty of ways to communicate with each other within a minute or two of needing to.

Rosin: Even though Signal’s encrypted?

Harris: Yeah. So the problem is this. There’s a couple problems. One, it’s encrypted, but it’s never been approved by the government for sharing classified or what’s called national-defense information. Now, to be clear, we talked to former security officials, former U.S. officials, who said, Yeah, we did use Signal in the government. We might use it to transmit sort of, um, certainly unclassified, not sensitive information. We might talk around something or, like, notify someone that you’re leaving a particular country. But this level of specificity—actual planning for an ongoing operation, the sharing of intelligence and information about strikes—that is clearly not what Signal’s intended for.

It’s very convenient, and it is relatively safe. I mean, I know, like, some officials who’ve traveled overseas in conflict zones who use it because they’re not near a U.S. embassy, let’s say, but it’s not meant for this kind of detailed planning which occurs as, you know, Mr. Waltz said, at the principals-committee level—that is done in the Situation Room, or that’s done at their various, you know, buildings where these people work.

Rosin: Just so I’m clear, what level of detail crosses the line? I know you don’t wanna say what they actually said about the campaign, but what kinds of details when you saw them were like: That would never happen.

Harris: So details like the number of aircraft that are involved, the kinds of munitions that are being dropped, specific times—

Rosin: That was on the chain?

Harris: Specific targets on the ground, um, you know, intelligence-related matters relating to the strike and to the targets, names of individuals—of U.S. officials—who should not have been put in an unclassified chain because of their status as intelligence officers. You know, you can kind of, like, you can—there’s probably six or seven different kinds of information that are arguably implicated under the rules and the law for how you’re supposed to handle this stuff.

Goldberg: By the way, a lot of it is just common sense. I mean, you read something, and you could tell the difference between strategic information and tactical information. We should deal with the Houthis—fine, right? We should deal—we should do X, Y, and Z, because the Houthis are a threat to commerce and American national-security interests.

This is what we’re gonna do to the Houthis in two hours is not information that the public should have. I mean, even as a reporter I say that, and, like, I’m fascinated. I want to know how they’re making decisions, why they’re making decisions. I wanna know after action why things happened, why they went right, why they went wrong, and so on.

But I don’t want—and I’ve been doing this for a while, as has Shane—I don’t want information before a kinetic action, before a strike of some sort that has to do with the practical aspects of that strike, information that if it got into the wrong hands could actually endanger the lives of Americans.

I mean, the north star for me and Shane and most normal people, normal reporters, is: Look, we don’t want to endanger the lives of American personnel in the field. And that’s why this was—that’s why the Saturday texting, the Saturday chain, was very, very different than the Friday: because it got very practical.

Rosin: When was the bombing campaign?

Goldberg: Saturday the 15th. The first bombs exploded in Yemen around 1:45 p.m. eastern time. I found out at 11:44 eastern time that it was happening.

Rosin: Got it. So just so I understand, it’s like, they’re revealing specificity of plans which are about to take place, which could put lives in danger, yes?

Goldberg: Okay, like, so here’s the thing that crossed my mind all throughout this, which is: Imagine if it weren’t me in that chain. But imagine if it were somebody—I mean, this sounds implausible, but it’s also implausible to include me in the chain—imagine it was somebody who was a Houthi.

Harris: Or an Iranian diplomat.

Goldberg: Or an Iranian diplomat, or a diplomat from another country who was a side deal with the Iranians. They literally would’ve known when things were going to happen.

Rosin: But I have to say: A journalist is no less dangerous. ’Cause you could have published those plans. So you’re not the best choice either.

Goldberg: Um, well, I, I’m the—yes.

Rosin: Of journalists, you’re an excellent choice.

Harris: I mean, a less scrupulous one—

Rosin: But a less scrupulous journalist.

Goldberg: No, no, I mean, and I’m sure there are journalists who disagree with my view, who take a kind of, I would call it nihilistic view, which is, like: Information is information; we should just put it all out there.

Rosin: Right.

Goldberg: And damn the torpedoes. I’m not—that’s not my thing.

Harris: There’s another reason why this was so dangerous that doesn’t have, doesn’t involve mistakenly adding a journalist to the thread. And that is that while Signal—I mean, you said it’s end-to-end encrypted; it’s very good and secure that way. That’s true. But the device that it’s on, right, is your phone. And while the iOS system is pretty good, nation-states—and here I’m talking about China in particular, which, remember, is behind a recent, you know, penetration of the telecom networks called Salt Typhoon—the phone in the pocket of every one of those national-security officials must be presumed to be a No. 1 target for a foreign intelligence service.

Rosin: Mm-hmm.

Harris: And there are kinds of malware that they could get implanted on that phone. There could be very expensive, very sophisticated stuff that could allow them to read the messages on the phone as they’re being typed. That’s why a system like Signal, even though it’s good end-to-end encryption, is not approved for sharing classified information. ’Cause it’s on your phone, which can be hacked.

Rosin: Right. So it’s obviously sloppy, reckless. Does it violate any laws?

Harris: So there are a couple that it might. Conceivably, it could violate the Espionage Act, which, despite the name, it’s not just about spying; it’s about the handling of what’s called national-defense information. So if this is considered national-defense information, there are provisions of that law governing how you transmit it, who’s allowed to have it—P.S. Someone like Jeff, who doesn’t have a security clearance? Not allowed to have it. So now these officials made this known to someone who wasn’t cleared—inadvertently, so that could be, you know, a mitigating piece of information. There’s also a provision of the Espionage Act that governs what’s called gross negligence in the handling or, more precisely, the mishandling of classified information. This was the provision that the Justice Department looked at when deciding whether to charge Hillary Clinton for using a private email server, and ultimately they did not, and this provision of the law has only, to my knowledge, been successfully used once to prosecute someone. Because it’s ambiguous—what do you mean by “gross negligence”? Was it grossly negligent to put it on Signal? Was it grossly negligent to add Jeff ? The commonsense reaction to that might be yes. So that’s possible that that could, you know, implicate maybe Mike Waltz or Pete Hegseth, even under the law. And then there’s also the Presidential Records Act and the Federal Records Act.

And in this case, I think these text messages are both federal records and presidential records, because they’re coming out of the White House in some cases. And the law says—

Goldberg: Literally, one of the participants is the elected vice president of the United States.

Harris: And another is the White House national security adviser. And we quoted an expert in the story, an expert on these laws, who said: Look, you know, if it’s a presidential record, you have to maintain it. And what that means is, in this case, a backup of these messages would need to be sent to some kind of government official account. If they were doing that, then they’re complying. But there are also DOD regulations about not putting classified information on an unclassified system, as clearly happened here as well.

So you’ve got a couple of laws, maybe two or three laws, provisions of those laws and regulations, that this activity would seem to violate.

Rosin: Well, Jeff, congratulations. You’re now part of the official Trump record—government official record. Okay, theories. I know you don’t know why this happened. Is there some possibility they wanted you to know? Have you run that through your head?

Goldberg: Oh, yeah. I ran all the possibilities through my head. You know, the funny thing is, when they’re having their policy conversation—policy disagreements—I was struck by the sophistication of the arguments. Some were, you know, sort of knee-jerk, anti-Europe kind of invective that one expects, but they were having a serious conversation about what to do about a challenging problem—a problem, by the way, they were left with by the Biden administration, which did not handle that situation well or adequately.

So they were, this is something they inherited, and they’re trying to work their way through it. As they were doing that, I was thinking to myself, Oh, maybe they want me to see this. So I write a story about how clever they are in dealing with the Houthis. And I thought, That’s very kind of a circular way of getting somebody to write something about—

Harris: Like, Waltz could just call you. He has your number.

Goldberg: They could just call me and say, I’d like to do an interview with you about our Yemen policy, and I’d be like, Great, let’s do it. So I couldn’t, I can’t—you know, Occam’s razor explains a lot of the world, and the explanation here is that it was heading into the weekend; they were out and about; things were happening in the Middle East that they had to stay in touch with; they have these amazing devices in their pockets, like we all do, where they can communicate with the world; they put together a group; they put it together sloppily; and they did it on something that they shouldn’t have done but for convenience; and, uh, that’s it. That’s what happened.

Rosin: So given that that can happen to the best of us and does happen to all of us all the time, is there—

Goldberg: You’re always, you’re always planning the bombings of countries on your phone with your podcast team.

Rosin: I mean, like, adding the wrong person to a text chain. So given that that happens to the best of us, can you draw any particular conclusions about the Trump administration? Like, does it reveal anything to you about them that’s specific, as opposed to just, you know, they’re sloppy like the rest of us?

Harris: I think there’s that aspect too, which, I mean, there is a little bit of a Who among us?, right? We’ve all done this—I mean, not about planning a war—but we know what this is like and how embarrassing and unintentional it can actually be. But what I do think this shows is a level of recklessness. There’s just no world in which a reasonable person serving these positions would think it’s okay to discuss this kind of active operation, I think, in this way. Now, there may be people who would challenge me on that, and there may be people who would say, Listen, it’s not as bad as it looks; they weren’t getting into totally the operational weeds—even though I think they actually were. You could make excuses for that, but just as a judgment matter, this was a bad one. It was a bad call, I think, to use Signal in this way. It’s not approved for this way. And you can see why it was such a bad call, because a horrible accident like this, from their perspective, can happen. But what I also think it reveals, too—and this is important to the policy debate—is there is not agreement in the administration over whether they’re doing the right thing with this action. There is widespread agreement, it seems, that they should make the Europeans try to pay for this military action, ’cause it’s mostly European goods that are moving through this part of the world. But when the vice president comes out and says, I disagree, and I don’t think that the president understands the implications for this and how it will affect his foreign policy—that’s quite striking.

And you see in the messages how they’re referring back to previous meetings that they had where it seemed to some people in the room like this issue was settled. But apparently it wasn’t. And they go on this kind of extended debate about: Well, should we wait a month? And then Stephen Miller, as Jeff said, comes in and says, No, the president said we’re doing this.

And so you see that there’s not clarity around the president’s decision making around the policy, and that is just—to be a fly on the wall for that is extraordinary. That’s very revealing about the policy process in this White House.

Rosin: You mean for such an important decision that there are last-minute disagreements that haven’t been buttoned up, that haven’t been hashed out, that haven’t gone through proper channels or, you know, like, thoughtfully resolved?

Goldberg: I think they were—I mean, apart from the fact that they were doing it on an insecure channel in the presence of the editor in chief of The Atlantic magazine—apart from those two technical issues, they were having a reasonable conversation that you would expect them to have.

And like I said, I was a little bit heartened that, Oh—they actually debate among themselves. They talk about this; they work through these things. They seem to be—as Shane pointed out, this is obviously the residue from other meetings that were taking place live and in person, where they’re still working out issues.

What I found—maybe just on a personal level or a, you know, a citizen level—disconcerting was when “S M,” who we assume is Stephen Miller or presume is Stephen Miller, when he comes in and says, Nah, I didn’t hear that. I heard the president say, “We’re doing it.” Thank you very much. Call it a day. And then everybody—

Harris: And no one disagrees.

Goldberg: And then everybody, including the secretary of defense, goes: Agree.

But I have to say, and I want to be very clear here, when I understood that this was real, I did remove myself from the group and began the process of writing this so that I could make the public aware, our reading public aware, that this government had, um, let’s just say poor digital hygiene. So it’s a very serious thing and I would rather not be engaged in that kind of text chain.

Rosin: Well, Jeff, Shane, thank you for joining us today.

Harris and Goldberg: Thank you.

Rosin: This episode of Radio Atlantic was produced by Kevin Townsend and edited by Claudina Ebeid. It was engineered by Rob Smierciak. Claudina Ebeid is the executive producer of Atlantic Audio, and Andrea Valdez is our managing editor. Listeners, if you like what you hear on Radio Atlantic, remember, you can support our work and the work of all Atlantic journalists when you subscribe to The Atlantic at TheAtlantic.com/podsub. That’s TheAtlantic.com/podsub. I’m Hanna Rosin—thank you for listening.