When worshippers first prayed at St. Peter’s Chapel 300 years ago, they probably thought about communing with Jesus as an expression of faith as opposed to a literal conversation.

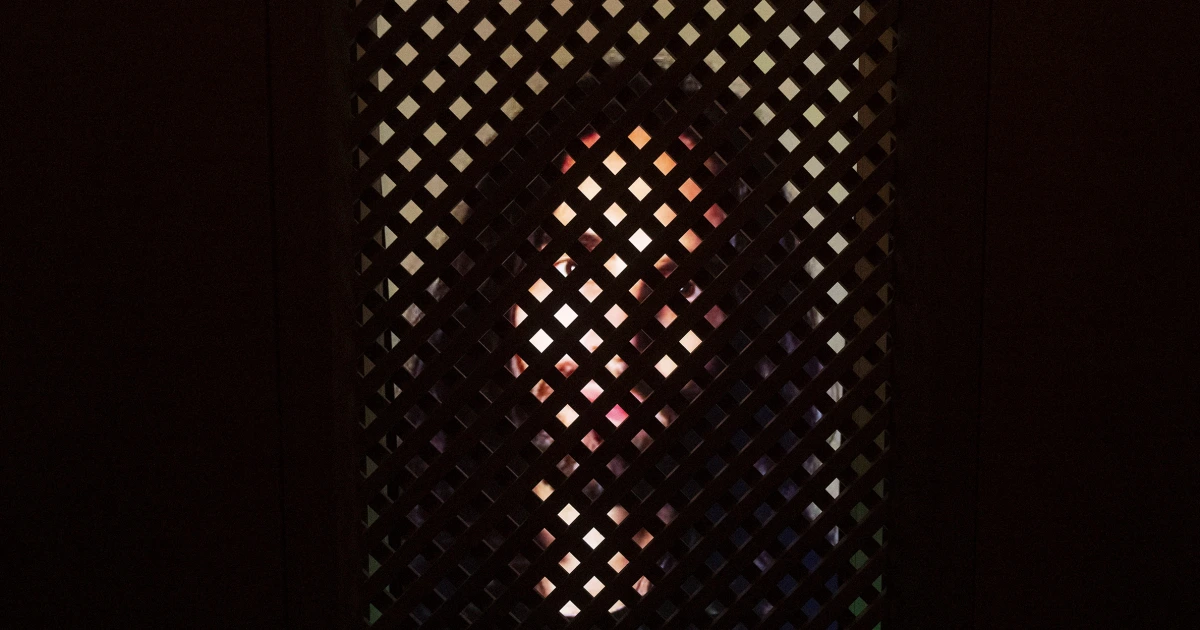

Three centuries on, at Switzerland’s oldest church, in the city of Lucerne, worshippers can now talk to a computer-generated avatar of the Son of God.

“Deus in machina” was developed by a team at the Immersive Realities Research Lab at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, as well the chapel’s theologian, Marco Schmid.

“Many people came to talk with him,” Schmid said, adding that around 900 conversations between the machine and people of “all ages” had been registered.

“What was really interesting to see [was] that the people really talked with him in a serious way,” Schmid said.

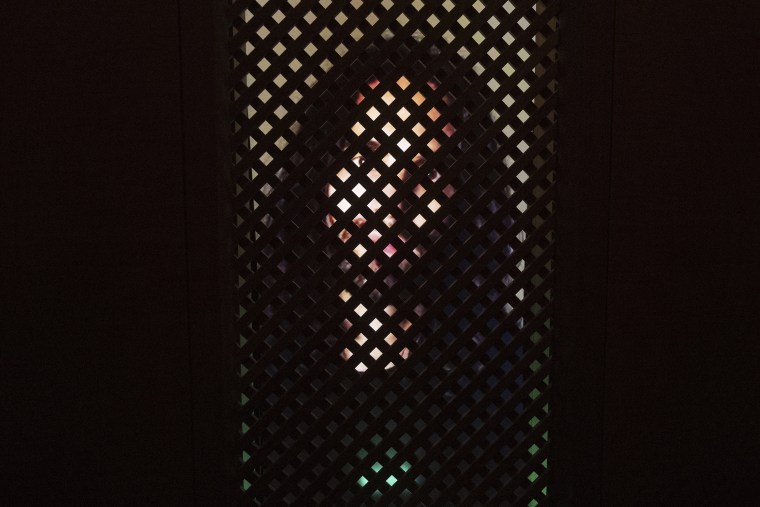

An AI Jesus has been installed in St. Peter’s Chapel in the old town of Lucerne, Switzerland.Urs Flueeler / Keystone via AP

Developed using artificial intelligence software, the machine emerged from two months of collaborative experiments.

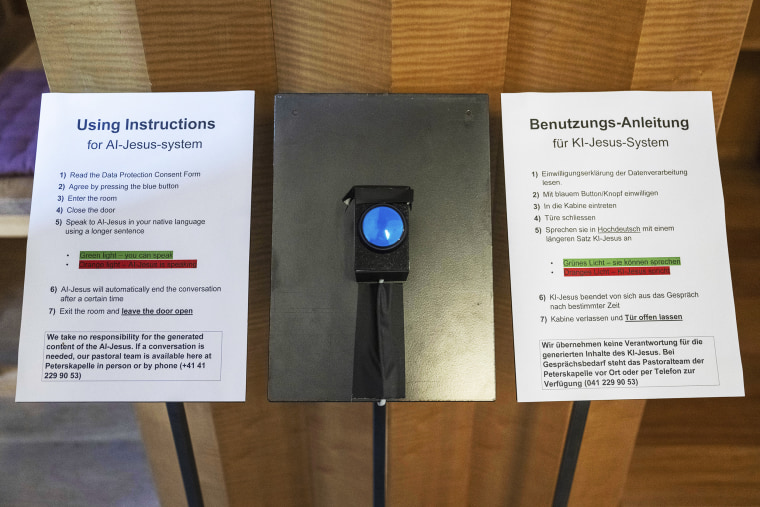

Participants enter a confessional booth and a lifelike avatar on a computer screen offers advice based on biblical scripture in more than 100 languages.

However, visitors are warned against sharing personal details and are required to acknowledge that their interactions with the avatar were at their own risk.

“This is not a confession; our aim is not to replicate a traditional confession,” Schmid said. Among the topics broached by visitors were true love, the afterlife, feelings of solitude, war and suffering in the world, as well as the existence of God.

The Catholic Church’s position on homosexuality and issues like the sexual abuse cases it has faced were also brought up.

Instructions for “Deus in machina” in Lucerne, Switzerland.Urs Flueeler / Keystone via AP

Most visitors described themselves as Christians, but agnostics, atheists, Muslims, Buddhists and Taoists also took part, according to a recap of the project released by the Catholic parish of Lucerne.

The majority were German speakers, but the AI Jesus — conversant in about 100 languages — also had conversations in Chinese, English, French, Hungarian, Italian, Russian, Spanish and other languages.

No specific safeguards were used because the technology can “respond fairly well to controversial topics,” said professor Philipp Haslbauer, who worked on the technical side of the project.

Noting that some on social media have called the project “blasphemous” or the “work of the devil,” he said, “If you read comments on the internet about it, some are very negative — which is scary.”

Brian Cheng

The Associated Press contributed.