FRIDAY, DECEMBER 6

■ Orion comes into good view low in the east-southeast after dinnertime now. And that means Gemini is also coming up to its left (for the world’s mid-northern latitudes). The head stars of the Gemini twins, Castor and Pollux, are at the left end of the Gemini constellation — one over the other, with Castor on top. The stick figures of the Twins are lying on their sides, with their feet toward Orion.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 7

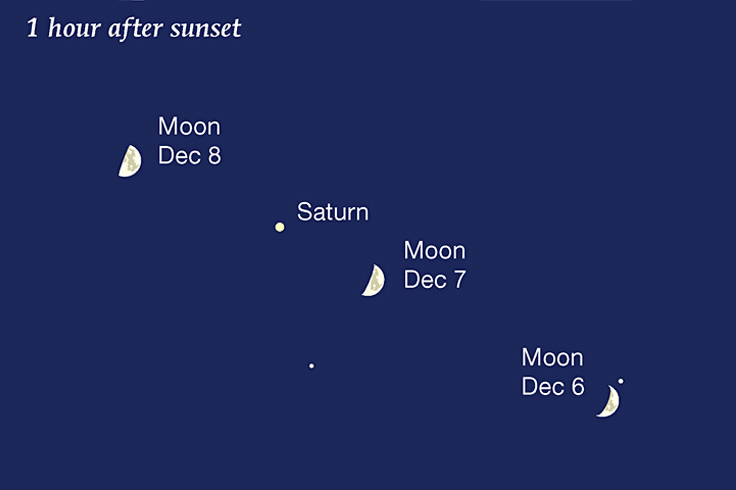

■ Saturn shines about 5° upper left of the Moon this evening, as shown below for North America. Although they may look like companions, Saturn is currently 3,900 times farther away. The Moon and Saturn are the nearest and farthest solar-system objects that are easily visible to the naked eye.

The Moon passes Saturn between the North American evenings of December 7th and 8th, while Fomalhaut looks on from below.

The Moon passes Saturn between the North American evenings of December 7th and 8th, while Fomalhaut looks on from below.

That star near the Moon on Friday the 6th is Delta Capricorni, magnitude 2.8. (The Moon’s apparent position against the background stars and planets will always vary a bit depending on your location.)

■ Jupiter is at opposition.

■ Earliest sunset of the year (if you’re near latitude 40° north). By the time of the solstice and longest night on December 21st, the Sun will set 3 minutes later than it does now. And the latest sunrise doesn’t come until January 4th. These slight discrepancies arise from the tilt of Earth’s axis and the ellipticity of Earth’s orbit.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 8

■ First-quarter Moon (exact at 10:27 a.m. EST on this date). The Moon shines upper left of Saturn this evening, as shown above.

■ After darkness is complete, can you make out the dim Circlet of Pisces less than a fist-width above the Moon? Its stars are only 4th and 5th magnitude. Cover the glary Moon with your finger to help them show.

Still too much light pollution? Try binoculars. The Circlet is 7° wide and 5° tall, slightly overspilling the field of view of typical binoculars. Sweep around just a little bit to pick up all seven of the Circlet’s stars.

The Circlet’s easternmost (leftmost) star is the carbon star TX Piscium. It’s strikingly redder in binoculars than ordinary “red” stars, which look more like orange or yellow-orange. We see carbon-rich stars through a red filter: C2 vapor in their atmospheres.

MONDAY, DECEMBER 9

■ This is the time of year when M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, passes your zenith soon after dinnertime (if you live in the mid-northern latitudes). It goes exactly through your zenith if you’re at north latitude 41°. The exact time depends on your longitude. Binoculars will show M31 just off the knee of the Andromeda constellation’s stick figure; see the big evening constellation chart in the center of Sky & Telescope.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10

■ This is the time of year when the Big Dipper lies down at its very lowest in the north right after dark. It’s entirely below the north horizon if you’re as far south as Miami.

But by 11 or midnight the Dipper stands straight up on its handle in fine view in the northeast, while Cassiopeia has wheeled down to the northwest to stand nearly upright on the bright end of its W shape.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 11

■ Have you ever watched Sirius rise? Find an open view right down to the east-southeast horizon, and watch for Sirius to come up about two fists at arm’s length below Orion’s vertical Belt. Sirius comes up around 8 or 9 p.m. now, depending on your location.

About 15 minutes before Sirius-rise, a lesser star comes up barely to the right of where Sirius will appear. This is Beta Canis Majoris or Mirzam. Its name means “the Announcer,” and what Mirzam announces is Sirius. You’re not likely to mistake them; the second-magnitude Announcer is only a twentieth as bright as the King of Stars soon to make his grand entry.

When a star is very low it tends to twinkle slowly, and often in vivid colors. Sirius is bright enough to show these effects well, especially with binoculars.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12

■ The Great Square of Pegasus floats its highest toward the south right after nightfall. In fact, if you’re as far south as Miami, it goes right across your zenith. Face south, crane your neck up, and the Square lies level like a box.

The Square’s right (western) edge points very far down toward Saturn and then Fomalhaut. Its eastern edge points less directly toward Beta Ceti (also known as Deneb Kaitos or Diphda), less far down.

Now descending farther: If you have a very good view down to a dark south horizon — and if you’re not much farther north than roughly New York, Denver, or Madrid — picture an equilateral triangle with Fomalhaut and Beta Ceti as its top two corners. Near where the third corner would be (just a touch to the right of that point) is Alpha Phoenicis, or Ankaa, in the constellation Phoenix. It’s magnitude 2.4, not very bright but the brightest thing in its area. It has a yellow-orange tint (binoculars help check). Have you ever seen anything of far-southern Phoenix before?

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 13

■ The Moon, a day from full, shines above Jupiter and Aldebaran at nightfall and lower left of the Pleiades, as shown below. Cover the glary Moon with your finger to help bring out the faint Pleiades stars.

As the evening grows late, this whole arrangement will climb higher and rotate clockwise. By about 11 p.m. the Pleiades will be directly right of the Moon, and Jupiter and Aldebaran will both be lower left of it.

■ Saturn’s two largest moons, Titan and Rhea, will form a telescopic “double star” 7 arcseconds apart as they pass each other this evening. Their minimum separation will come around 5:59 p.m. EST, just after dark for eastern North America. Rhea will be south of brighter Titan. Watch them pulling apart for the rest of the evening, or already doing so right after dark if you’re observing from a location farther west.

Titan and Rhea are magnitudes 8.5 and 10.0, respectively. Pick them up about one ring-length to Saturn’s celestial west, then switch to high power.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 14

■ The full Moon shines all night. It’s exactly full at 4:o2 a.m. Sunday morning EST. By no surprise, the Moon this evening just a few hours before its opposition, and Jupiter just a week past its opposition, shine close together in the sky: opposite the Sun.

■ The Moon forms line with Jupiter and Aldebaran to its right, as shown above. For most of the night in most places, the line will gently curve. But the Moon will make an exact straight line with Jupiter and Aldebaran in late evening for most of eastern and central North America, and earlier in the evening for most of western North America.

■ By midnight the Moon will be very high, not far from the zenith. The full Moon of the Christmas season rides higher across the sky at midnight than at any other time of year, thus “giving lustre of midday to objects below.”

Why? December is the month of the solstice, when the Sun is farthest south in the sky. So, this is when the full Moon (opposite the Sun) is farthest north. In making its way across the night sky, the December full Moon is a pale, cold imitation of the hot June Sun crossing the daytime sky a half a year ago.

■ The Geminid meteor shower, often the richest of the year, should be at its peak late tonight. But the full moonlight will hide many of its meteors, leaving only the brightest ones to shine through. In the evening the visible meteors will be fewer still, but those that do appear will be Earth-grazers skimming far across the top of the atmosphere.

The best direction to watch? Wherever your sky is darkest and the Moon can be kept completely out of your view.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 15

■ The Summer Triangle is sinking lower in the west, and Altair is the first of its stars to go (for mid-northern skywatchers).

Start by spotting bright Vega, magnitude zero, the brightest star in the northwest right after dark. The brightest one above Vega is Deneb. Altair, the Triangle’s third star, is farther to Vega’s left or lower left. How late into the night, and into the advancing season, can you keep Altair in view?

Mercury spends most of this week buried out of sight in the glow of sunrise. Next week it will emerge to become much easier in the dawn.

Venus (magnitude –4.3, in Capricornus), shines high in the southwest in evening twilight, higher every week. It remains up for nearly two hours after dark before setting. In a telescope Venus is gibbous (now only 2/3 sunlit) and 19 arcseconds from pole to pole.

Mars (about magnitude –0.7, in Cancer) rises in the east-northeast around 8 p.m. It’s near its eastern stationary point, pre-opposition. So it still forms the right angle of a rough right triangle with Castor and Pollux above it and Procyon to its right. Mars is 50° east along the ecliptic from brighter Jupiter.

All week Mars remains 2° or 3° above M44, the Beehive star cluster, when seen in the east in late evening. Use binoculars.

Mars shows best in a telescope when very high toward the southeast or south after midnight. It has enlarged to 12 arcseconds in apparent diameter, on its way to a relatively distant (aphelic) opposition on January 15th. It will be closest to Earth three days before that, with an apparent diameter of 14.6 arcseconds.

Jupiter is just past its December 7th opposition, shining at a bright magnitude –2.8 in Taurus. Spot it fairly low in the east-northeast as twilight fades. As dusk deepens, watch for Aldebaran and slightly fainter El Nath (Beta Tauri) to come into view equidistant from Jupiter to its right and left. Jupiter will cross the line between the two stars on December 10th. Watch its progress with respect to them from night to night by holding a straightedge up to the row of three.

Jupiter is at its telescopic best when very high toward the southeast or south after 9 or 10 p.m. It’s still 48 arcseconds wide in a telescope.

Saturn, magnitude +1.0 in Aquarius, glows highest in the south soon after dark. Don’t confuse it with Fomalhaut twinkling two fists below it. Saturn is now 40° east of Venus along the ecliptic. Watch them close in on each other toward their conjunction on January 18th, when they’ll pass each other by 2.2°.

Saturn on November 2nd, imaged by Christopher Go. North is up. Go also caught a couple other objects here. The dark dot near the lower left limb is the shadow of Rhea, Saturn’s second-largest moon. Rhea itself is the white dot in the foreground of Saturn’s south pole (bottom). The speck above Saturn’s rings on the right is Tethys.

Saturn on November 2nd, imaged by Christopher Go. North is up. Go also caught a couple other objects here. The dark dot near the lower left limb is the shadow of Rhea, Saturn’s second-largest moon. Rhea itself is the white dot in the foreground of Saturn’s south pole (bottom). The speck above Saturn’s rings on the right is Tethys.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, at the Taurus-Aries border) is high in the southeast during evening, about 7° from the Pleiades. You’ll need a good finder chart to tell it from its surrounding faint stars, such as in the November Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.9, near the Circlet of Pisces) is high in the south after dark, 14° east of Saturn. Again you’ll need a proper finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

The Pocket Sky Atlas plots 30,796 stars to magnitude 7.6, and hundreds of telescopic galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae among them. Shown here is the Jumbo Edition, which is in hard covers and enlarged for easier reading outdoors by red flashlight. Sample charts. More about the current editions.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5, and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), andUranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]()

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770