Concern over the climate crisis may evaporate in the White House from January, but its financial costs are now starkly apparent to Americans in the form of soaring home insurance premiums – with those in the riskiest areas for floods, storms and wildfires suffering the steepest rises of all.

A mounting toll of severe hurricanes, floods, fires and other extreme events has caused average premiums to leap since 2020, with parts of the US most prone to disasters bearing the brunt. A climate crisis is starting to stir an insurance crisis.

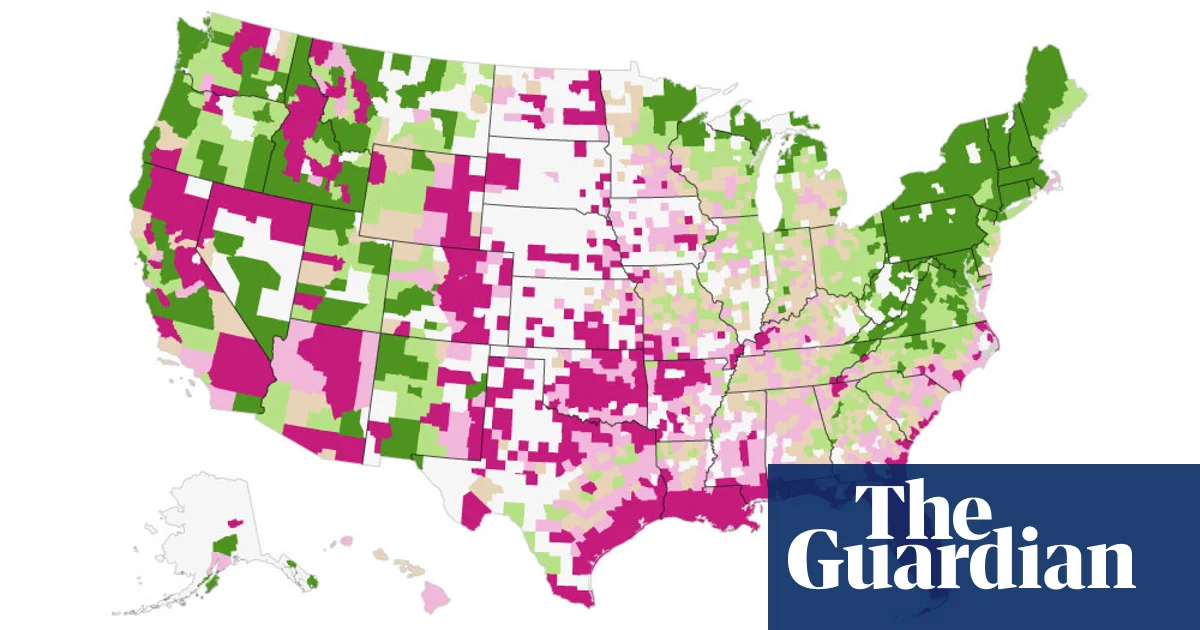

Across all US counties, those in the top fifth for climate-driven disaster risk saw home premiums leap by 22% in just three years to 2023, compared to an overall average of a 13% rise in real terms, research of mortgage payment data has found. The Guardian has analyzed the study’s data to illustrate the places in the US at highest risk from disasters and insurance hikes.

“This has been the canary in the climate coalmine, and it’s now hitting households’ pocketbooks,” said Ben Keys, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and co-author of the research. “You can deny climate change for whatever motivations you have but when insurance is going up because you live in a risky area, that’s hard to deny.”

Keys said there is a “tight correlation” between premium rises and counties deemed most at risk from a metric drawn from past disasters combined with modeling of future events exacerbated by the climate crisis.

Heightened disaster risk now results in a $500 jump in premiums, on average, for households, Keys’s paper finds. People looking for home insurance, required for a mortgage, are now facing tangible climate costs even before they have to pay out for flooding cover, which is typically separate from home policies.

“The cost of living in harm’s way has gone up disproportionately,” said Keys. “We are seeing the first broad-based direct cost of climate change for homeowners because of these insurance increases.”

Across the US there are insurance-rise hotspots, ranging from Teton county, Wyoming, home of the Jackson Hole ski area, to Assumption parish, near the flat, fraying coast of Louisiana. Such places have seen raises because of major fires or floods, others for smaller but more frequent impacts and some primarily for unrelated factors.

“We are getting more of these secondary events like hail storms and extreme rainfall that mean you get a big insurance cost increase in Minnesota even though you aren’t hit by big hurricanes,” said Andrew Hoffman, an expert in environmental and sustainability policy at the University of Michigan.

Line chart, with a dark pink line moving the most up the to the right

As such damaging events pile up around the world, the insurance industry is looking at the climate crisis as a threat like no other. In October, the insurance giant Axa ranked climate change as the biggest risk facing the industry globally, above geopolitical instability and cyber and AI issues, for the third year in a row.

“We are getting more unpredictability that insurance companies don’t like, a rise in construction costs, and an increase in the number of assets located in at-risk places,” Hoffman said. “A lot of things are coming together.”

If there is an epicenter of disaster risk and ballooning insurance in the US, it’s to be found along the Gulf of Mexico coast and, in particular, Florida, the state where home insurance costs more than $11,000 a year on average, surging by 42% just in 2023. “Florida is a creature unto itself,” said Keys. “It has had so many waves of storms and insurers going bust that the risk exposure is kind of staggering.”

More than a dozen insurers have left Florida in the past seven years amid a stampede of disasters, placing strain upon a state-supported backstop insurance system that is now “not solvent” according to Ron DeSantis, Florida’s governor.

DeSantis has opted to pretend a key driver of this problem doesn’t exist, deleting mention of climate change from state law in May. Donald Trump is similarly expected to remove climate considerations from US government agencies and federally-backed projects that face higher risks because of climate change.

Florida’s state Citizens Property Insurance Corporation has just over 1m insurance policies on its books, although its trying to offload many of these on to private insurers. Citizens, which wants to hike rates by 14%, has so far denied nearly 30% of claims relating to Hurricane Helene and about 6% of the claims from Hurricane Milton – two major storms that recently hit Florida in quick succession.

“The system is sustainable,” said a Citizens spokesman, pointing out that by law surcharges can be placed against other Florida insurance policyholders if it runs out of money. “As Florida’s insurer of last resort, Citizens will be there for policyholders who cannot find comparable coverage in the private market.”

But Helene and Milton highlighted broader holes that are appearing in the insurance market, with just a quarter of homes in Pinellas county, Florida’s hardest-hit county, having flood insurance. In Asheville, North Carolina, which was devastated by Helene, just 1% of homeowners had flood insurance.

“Though approximately 90% of all US natural disasters involve flooding, many homeowners still are unaware that a standard homeowners policy doesn’t cover flood damage,” said Dale Porfilio, chief insurance officer of the Insurance Information Institute.

An arrow chart, most of the lines at the top are shades of pink.

Even within the home insurance market, the rising costs are starting to bite, with 10% of American homeowners now going without and nearly a third of losses from natural disasters going uninsured. Research has found that rising premiums also worsen the risk that people miss mortgage repayments, making them vulnerable to losing their homes entirely.

“I can understand why people in states like Florida are hurting because suddenly their premiums are double or triple what they were, it’s a huge shock,” said Parinitha Sastry, a finance expert at Columbia Business School whose research has shown that low-quality, fragile insurers are stepping in to replace those that have departed Florida.

“Regulators are grappling with this trade-off with the quality of insurance and the affordability of the insurance. It’s a tough balancing act.”

But will these pressures on the insurance market impact broader trends, whereby the US population is generally shifting southwards towards warm weather, affordable housing and jobs, even though these are places most at risk from the climate crisis?

There is conflicting research on this, with some studies suggesting climate risks are often ignored by the public, while others point to a reverse “snowbird” effect taking place where some retirees are fleeing the increasingly oppressive heat and storms. Insurance is now growing to be a major consideration, though, rather than incidental household cost.

“The cost of insurance will start to change people equations,” said Hoffman. “Somewhere like Florida is warm, there’s no income tax, it’s a strong draw for seniors. Insurance might not stop people moving there, but if you’re selling you might not get any buyers.

“Insurance is so important for the economy. Sooner or later we are going to have to have a serious meetings of minds about not building in certain places because it just won’t get insurance.”