In this guest essay for the New York Times, Dr. Chan explained 5 key points that suggest that the COVID pandemic likely started in a lab. The essay was excellently written and supported by great figures. Still, it does not mention some more complex, but very clear evidence for a lab origin, which is why I wrote this article.

I was not involved in the DEFUSE project, I have never made a virus more infectious or more deadly, but I use almost the same methods and the same bioengineering tools that they used almost every day.

To answer the question of where SARS-CoV-2 came from, I approached each piece of evidence by asking three questions:

1) How did virologists from Wuhan and their collaborators manipulate viruses in the past, and what sort of manipulations did they plan around 2019?

2) Do we find these changes in the genome of SARS-CoV-2?

3) How likely is it that these changes could occur through natural evolution?

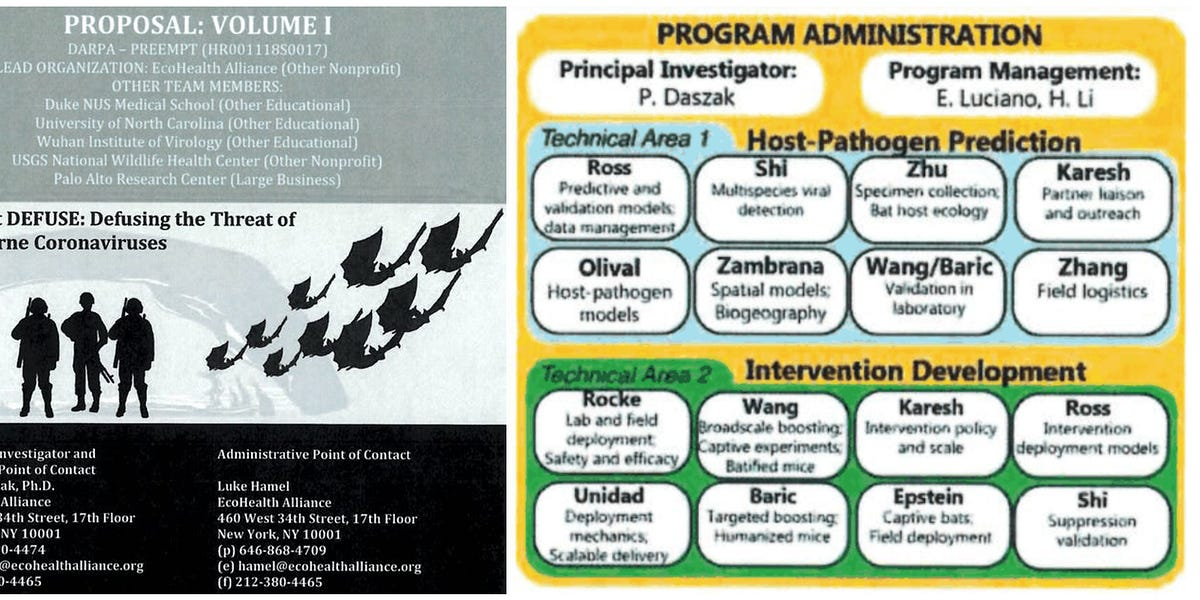

To address the first question, I analyzed published papers, a leaked international research proposal (DEFUSE) and the respective proposal drafts of virologists working in Wuhan and their international collaborators.

The DEFUSE proposal was co-written by virologists and bioengineers from the US, China and Singapore and led by the US non-profit organization Ecohealth Alliance. The principal investigator of DEFUSE recently said that they received funding for some parts of the the proposal, and virologists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology had funding from very similar projects.

These 10 pieces of evidence in my opinion prove beyond reasonable doubt that SARS-CoV-2 was a lab manipulated virus:

Historically, zoonotic events occur when animals carrying high viral loads come into direct contact with humans. The DEFUSE drafts include a map illustrating the “host-pathogen niche,” designed to estimate the where SARS-related coronaviruses are likely to spill over into human populations. I overlaid national borders on this map, highlighting where the two viruses most closely related to SARS-CoV-2 – RaTG13 and BANAL-20-52 – were found. These viruses were sampled from bats in an abandoned mine shaft in Yunnan province, China, and a cave in Laos, respectively.

Many large cities are located within provinces where SARS-related and SARS-CoV-2-related viruses naturally occur, alongside thousands of animal markets. If SARS-CoV-2 originated from a zoonotic event, we would expect the first human cases to appear near these viral reservoirs. Furthermore, if the virus reached Wuhan through a chain of infected intermediate hosts, we would expect evidence of this, such as infected animals at fur farms or among animal handlers. However, no such evidence has been reported.

Alternatively, if the pandemic started due to a lab accident, we would expect the outbreak to occur where research on related viruses was most concentrated. The following graph shows which of the 20 largest cities in mainland China conducted the most research on bat coronaviruses. Between 2006 and 2018, virologists in Wuhan published significantly more papers on bat coronaviruses than those in any other major Chinese city—over five times more than expected for a city of its size. We know that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) transported RaTG13 from Yunnan to Wuhan in a sealed container. Additionally, despite denying to do so, Ecohealth Alliance employees sampled bat coronaviruses in Laos where BANAL-20-52 was found and send them to the WIV. According to DEFUSE, WIV had “>180 bat SARSr-CoV (SARS-related coronavirus) strains sequenced in prior work and not yet examined for spillover potential”. Such a collection requires tens of thousands of samples and years of sequencing work.

By comparison, only about twice as many bat coronaviruses were published across all of Europe between 1968 and 2020. Access to the relevant WIV databases was restricted in the fall of 2019, and even the WHO commission investigating the origins of SARS-CoV-2 was denied access to these records.

In conclusion, Wuhan is precisely the city where a lab accident involving a virus like SARS-CoV-2 would be most likely to occur, whereas a zoonotic event would be expected in Yunnan, Guizhou or Guanxi or neighboring countries.

The two main papers in science that supposedly prove a market origin contain numerous logical and technical errors. The journal had to print corrections (erratums) for both of them. But even ignoring those methodical errors, the core assumptions in the papers did not make much sense.

One obvious explanation for finding early samples with a connection to the market is that SARS-CoV-1 was found at wild animal markets, so it made a lot of sense that the local center for disease control focussed on patients with a market connection when looking for a new virus. There are documents that instructed doctors to focus on such patients. And we do know that some data on early cases was deleted. If people got first infected at the market and then infected others, the secondary infections should in average be further away from the market than the people with the direct link. This was not the case. In addition to that, there were BSL2 labs working on novel viruses directly next to the market which the science papers simply don’t show.

Dr. Chan also nicely shows that the earliest cases had no conections to the market. All the samples at the market were collected at least one month after the outbreak. Everyone who has ever been to a city with more than 10 mio inhabitants knows that thousands of them will commute way further than the four kilometers between the market and the (here irrelevant) BSL4 lab every day. Even ignoring the coding errors, it makes no sense to assume that viral lineages that differ by only two mutations must have come from two different species jumps. Two or even three mutations can often occur in indivdual patients, as observed 11 times during the Diamond Princes cruise ship outbreak. Also, in contrast to species jumps or human to human infections, where usually only few viruses reach the new host in a tiny droplet, lab accidents can leak lots of infectious material at once, one leak can contain pathogens with different mutations. And we do know that viruses found in different intermediate host animals can differ by up to 18 mutations, and by approximately 50 mutation from viruses found in humans.

While it is important to consider the potential motivations of Chinese officials to conceal the origins of the pandemic, for instance, if it were linked to a fur farm, the evidence for a zoonotic origin remains weak. As Dr. Chan points out, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic differs from related viruses like SARS-CoV-1 and MERS in several key ways:

- No infected animals have been identified.

- The earliest known cases had no exposure to live animals.

- Antibodies have not been found in animals or among animal traders.

- Direct ancestral variants of the virus have not been detected in animals.

- There has been no documented trade of host animals between areas where bats harbor closely related viruses and the outbreak site.

To illustrate the lack of evidence for a natural intermediate host, let’s examine the raccoon dog, the most frequently discussed candidate. SARS-CoV-2 started spreading from humans into deer and minks after evolving a key stabilizing mutation in the spike protein (D614G) very early during the pandemic. In contrast, not one wild raccoon dog infected with SARS-CoV-2 has ever been found. No one even knows if raccoon dogs can be infected with the first SARS-CoV-2 lineage. The only study that assessed the susceptibility of raccoon dogs did not use the original Wuhan strain to infect the animals, but one with the D614G mutation. Even with the D614G mutations, 3 of the 9 raccoon dogs which got 2 ml of virus solution pipetted directly into their noses did not get infected. None got any severe disease symptoms such as fever, which was observed in the intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-1. The contact animals were kept in cages next to the manually infected raccoon dogs. They never reached the same titers as the infected ones, and cleared the virus likely at the same time.

Intermediate hosts are typically species that shed large quantities of a virus. In contrast, the viral titers in raccoon dogs were about 10,000 fold lower as compared to infected humans! This means that an individual would need to be in a room with approximately 10,000 raccoon dogs to face a similar infection risk as with just one infected human. Moreover, discussions around raccoon dogs at the Wuhan Seafood Market often focus on a very small number of animals, further highlighting the inadequacy of the evidence for this potential intermediate host.

A common misconception is that because Wuhan is home to China’s only Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory, all work on bat coronaviruses must have been conducted in such high-security labs, where accidents are rare. However, one DEFUSE virologist revealed that experiments on bat coronaviruses were also carried out at Biosafety Level 2 (BSL-2). Unlike the extensive protective measures required in BSL-3 and BSL-4 labs, BSL-2 lacks stringent precautions – even basic face masks, like those worn during the pandemic for everyday activities, are not even mandatory.

How an FCS makes viruses more lethal

Furin is a protease, a protein that cleaves other proteins, which allows the spike protein of viruses like SARS-CoV-2 to more effectively infect cells. Related viruses usually replicate in the intestinal tract of bats and are isolated from fecal samples. Here, proteases like trypsin that help to digest proteins in the food can cleave the spike protein. Since trypsin is only present in the digestive system, some MERS-related viruses that lack an FCS cannot infect cells outside of this system, such as lung cells, unless trypsin is added to the experiment. TMPRSS2 is another protease that cleaves SARS-CoV-2 spikes and is additionally expressed in kidneys and endocrine and reproductive organs (not shown). However, unlike trypsin or TMPRSS2, Furin is present in almost all internal organs, including critical ones such as the lungs and brain. This wide distribution of furin allows viruses with an FCS to spread via the air and infect various organs, including those where damage can be permanent or lethal. For example, neurons cannot regenerate after infection, whereas intestinal cells can. An FCS enables other coronaviruses like MERS to infect a large variety of tissues, but also helps a large variety of other viruses to infect critical organs and to cause severe diseases. Virologists in the Netherlands have inserted a FCS into a rather harmless bird flu virus, which then also infected brains and hearts of chickens, making it much more lethal. Similarly, when a synthetic variant of SARS-CoV-2 had its FCS removed, it stopped causing disease symptoms in hamsters. In conclusion, the FCS enabled this virus to rapidly spread via the air, to be be more lethal and to cause severe and lasting symptoms in some patients.

Why the FCS in SARS-CoV-2 was with almost absolute certainly engineered

As noted, some MERS-related coronaviruses (Merbecoviruses) naturally have a FCS. However, within the family of SARS-related coronaviruses (Sarbecoviruses), SARS-CoV-2 is the only one out of more than ~1500 viruses with such a FCS. The FCS in SARS-CoV-2 resulted from an insertion of 12 nucleotides (“letters” in the genome) that add 4 amino acids (protein building blocks) to a very specific part of the spike protein, the S1/S2 interface, which consists of only 5-10 amino acids. The consensus motif of a FCS is RXXR, (two arginines with variable amino acids in between, usually one more R or K). SARS-CoV-2 related viruses only have a single arginine in the S1/S2 interface, which is also part of the FCS in SARS-CoV-2. The FCS in SARS-CoV-2 emerged through a insertion of these nucleotides, which are far less frequent than mutations, but can happen naturally in such viruses.

The question is: how likely is it that such a precise, FCS-generating insertion happened randomly? Out of close to 30.000 nucleotides in the genome of SARS-CoV-2, the insertion that generated the FCS occurred exactly at the arginine in the S1/S2 interface. Despite insisting that “SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus” in the most cited publication on the origin of SARS-CoV-2, one of the authors described the inserted FCS to his colleagues as follows: “a perfect insertion… that adds the furin site”. He “can’t think of a plausible natural scenario where you get from the bat virus or one very similar to it to nCoV where you insert exactly 4 amino acids 12 nucleotide that all have to be added at the exact same time to gain this function – that and you don’t change any other amino acid in S2? I just can’t figure out how this gets accomplished in nature.”

If we consider the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 emerged from a lab accident during a DEFUSE-like project, we can ask: Have virologists previously added an FCS to the spike protein of sarbecoviruses? The answer is yes. Did DEFUSE-affiliated virologists specifically add an FCS to bat coronaviruses in the past? Again, the answer is yes. Are plans to add a FCS to bat coronaviruses mentioned in DEFUSE? Yes, they wrote: “We will analyze all SARSr-CoV S gene sequences for appropriately conserved proteolytic cleavage sites in S2 and for the presence of potential furin cleavage sites. … Where clear mismatches occur, we will introduce appropriate human-specific cleavage sites”. While it is somewhat unclear what a “human-specific” FCS is, what they most likely meant is one found in humans. So does the one in SARS-CoV-2 match a FCS found in humans? Yes, it does, in 8 out 8 amino acids. And does the DEFUSE proposal specifically mention to add the FCS to the S1/S2 interface where the FCS is found in SARS-CoV-2? Yes, in the drafts, in a graph. Some virologists have argued that one would not use this type of out-of-frame insertion, but this is speculative, there can be reasons to do this. An additional suspicious feature is that both arginines (R) in the SARS-CoV-2 FCS are coded by a nucleotide sequence extremely rare in bat coronaviruses, but considered ideal for use in humans by some publications.

In conclusion, an FCS did not naturally evolve and persist in any of the roughly 1,500 Sarbecoviruses over the course of more than 1,000 years. The first time one appears is exactly where, exactly how and shortly after, virologists proposed introducing it.

To understand the implications of this finding, we have to briefly discuss key characteristics of an ideal intermediate host species. Those include:

- High Susceptibility: The virus should be able to efficiently infect the intermediate host species, which in turn should produce high viral titers.

- Sustained Viral Levels: The intermediate host species must be able to maintain high viral levels over several passages or through an infection chain.

- Local Abundance: The species should be present in higher than average frequencies at the outbreak location.

- Close Contact with Humans: There should be regular interaction with human populations.

- Genetic Relation: The virus in the intermediate host should be genetically “in between” human lineages and viral lineages found in other animals such as bats.

Except for the close contact criterion, none of these characteristics are met by raccoon dogs or any of the other potential intermediate hosts discussed by virologists. If we consider the possibility that DEFUSE experiments were conducted, what might constitute an “intermediate host” in a lab accident scenario?

The DEFUSE proposal mentions several potential intermediate hosts: their “recombinant viruses” were to “be recovered in Vero cells, or in mouse cells over-expressing human, bat or civet ACE2 receptors”.

Vero cell lines are derived from African green monkeys and cannot produce interferon, which makes them highly susceptible to all sorts of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. They were frequently used in Wuhan, for example to generate recombinant viruses. And a team of Hungarian scientists discovered Vero cell line DNA in a sample that also contained one or more SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Some of the mutations in that SARS-CoV-2 sample exactly matched the mutations one would expect to find in a SARS-CoV-2 lineage ancestral to all human SARS-CoV-2 lineages. In contrast, just one sample from the Huanan Seafood Market was from the later lineage A, and did not contain animal mitochondrial DNA. All other samples were from the much later lineage B.

The DEFUSE proposal explicitly outlined the companies they intended to use for sequencing their samples. Notably, one of these companies, Sangon Biotech, was responsible for sequencing the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 sample that contained Vero DNA. It is important to highlight that some unknown scientists attempted to suppress this crucial publication by rejecting its posting on a preprint server, while the NIH sought to delete the records of these samples.

However, there are limitations to consider: the contaminating reads were inadvertently released alongside data from an experiment involving soil samples collected in Antarctica, and the exact sequencing date remains unknown. Additionally, the virological experiment for which these samples were sequenced has never been published. Other laboratory cell lines (such as CHO cells) and human DNA were also present in the experiment, along with reads from SARS-CoV-2 genomes exhibiting rare mutations and deletions. The DEFUSE proposal specifically mentioned an interest in deletions in the spike protein and indicated plans to grow viruses on human airway epithelium, which would account for the presence of human reads. They also aimed to characterize the binding of their viruses to the human ACE2 receptor, for which CHO cells could be utilized.

In my opinion, the most plausible explanation for the mixture of early genomes, later mutations, and standard laboratory cell lines is that virologists conducted precisely the experiments outlined in the DEFUSE proposal. Upon noticing a viral outbreak in their city, they became concerned that the bat coronavirus responsible for it might have originated from their laboratory. Consequently, they sent all their frozen samples from related experiments to Sangon Biotech for sequencing. As this is a very technical detail, they failed to realize that their results could leak as contaminating reads into other, none-censored experiments conducted on the same sequencing machine. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that SARS-CoV-2 was generated in a Vero lab cell line, which exhibits all the key features of an intermediate host.

One of the most striking differences between the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and previous coronavirus outbreaks is the speed at which SARS-CoV-2 spread globally. Research on SARS-CoV-1 has shown that a virus’s infectivity is closely related to its ability to bind to human receptors via the spike protein. A study modeling the binding affinities of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins to various species’ receptors found that SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein binds more effectively to human ACE2 than to the ACE2 receptors of bats, pangolins, or a wide range of other animals. This level of adaptation to the human receptor is unusual, particularly considering that one of the earliest samples taken from humans already exhibited such a close fit. This level of adaptation has never been observed in related MERS or SARS-1 outbreaks, even after multiple zoonotic events and more than six months of human infections.

In 2017, researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) published a paper detailing their work on recombinant viruses, in which they replaced the spike gene with genes from eight other viruses. In drafts of the DEFUSE proposal, they outlined a more sophisticated approach, intending “to model RBD, ACE2 interaction (3D protein modeling)”. The RBD (receptor-binding domain) is the segment of the spike protein that directly interacts with the human ACE2 receptor. They noted that “through recombination, it is possible to insert the correct RBD into a strain with 25% variation, allowing the virus to enter human cells and replicate.” They planned to screen 15-16 viruses to identify which “7 or 8” strains to prioritize. They aimed to test the RBDs predicted to bind well to human ACE2 “individually and in combination” with new furin cleavage sites (FCSs) in “3-5” newly generated recombinant viruses each year.

An RBD-chimeric virus would be expected to exhibit a significantly higher frequency of new amino acids in the RBD that are absent in closely related non-chimeric viruses. It is also plausible that a “RBD template virus” existed, containing a nearly identical RBD while exhibiting considerable divergence in the rest of the viral genome. Initially, DEFUSE virologists claimed that RaTG13 was sequenced in 2020, but they later admitted that they had access to its full sequence since 2017.

Using free alignment and DNA analysis tools, everyone can assess the divergence between RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 across individual viral proteins, including the segments mentioned in DEFUSE. Excluding the FCS and RBD, the proteins are highly similar, with an average of only 1% difference in amino acids. In stark contrast, 60% of the amino acids in the short FCS (RRARS) differ, along with over 20% of the amino acids in the RBD.

There are also known potential template viruses from which virologists could have copied the RBD, such as a virus identified in a pangolin in Malaya in 2019 (although the origin is debated) or a Banal-20-52-like virus.

Viruses can naturally exchange segments of their genomes through a process known as recombination, which has previously resulted in the emergence of new chimeric viruses. Several Omicron variants are likely products of such recombination events. However, there are notable differences between these natural occurrences and what we observe in the first SARS-CoV-2 lineage.

First, the precision of the genomic changes in SARS-CoV-2 is remarkable. Such a precise replacement of only the receptor-binding domain (RBD) seems to be highly unusual. In contrast, the DEFUSE virologists have published and patented chimeric viruses with precisely replaced RBDs in the past.

Second, for natural recombination to take place, both viruses must infect the same cell simultaneously. This is more likely when the viruses have similar spike proteins, as seen with the billions of human infections during the emergence of recombinant Omicron variants. However, the wild-type RaTG13 spike protein is largely ineffective at infecting cells that express the human ACE2 receptor.

Third, the “RBD-donor” viruses, such as pan-CoV GD_1 or Banal-20-52, were identified in Laos and Malaya, while the “recipient virus,” RaTG13, was found in Yunnan, China. These are huge distances, much further than bats naturally migrate, and the segments contain very mutations, which suggest that there was not a lot of time for migration to occur.

Given the precision in which the RBD was replaced, the differences in receptor usage, and the geographical distance between these viruses, the likelihood of a natural recombination event is extremely low. The only known location where both viruses from Laos and the recipient virus RaTG13 were present is a virology lab in Wuha

One of the plans in the DEFUSE proposal was to develop vaccines for bats to reduce spillover risks into humans. Vaccinating wild animals such as bats comes with certain challenges, as the vaccine cannot be directly injected into thousands of bats, and thus not permanently cooled until administration. Many common vaccine formulations would not work in such a setting. DEFUSE virologists planned “to produce codon optimized, stabilized and purified prefusion SARS-CoV glycoprotein ectodomains… used for inclusion in delivery matrices (e.g purified powders, dextran beads, gels).

Codon optimization is a technique to increase protein production yields by adapting the DNA sequence of the protein to the cells used for protein production. Proteins are often much more stable than e.g. virus-based or mRNA-based vaccines, and thus a theoretically good format for a bat vaccination project. And the powders, gels or beads were supposed to be fed to the bats, which is obviously much more feasible than injecting bats. However, SARS related virus spikes are protein trimers: they are formed from three identical spike monomer chains anchored in the viral membrane. Likely to ensure that pure spike monomers form trimers in the absence of membranes, DEFUSE virologists wanted to add a “C-terminal T4 fibritin trimerization domain” and showed a “Fd” trimerization domain in another graph. They cited this paper describing the use of trimerization domains for MERS vaccines.

Chinese scientists who had collaborated with DEFUSE virologists published how such synthetic spike proteins can be designed for SARS-CoV-1 in 2004. They used several genetic elements to achieve high production yields (briefly: a plasmid called pcDNA3.1, a tissue plasminogen activator (Tpa) signal peptide, and codon-optimization for a human cell line).

Exactly such codon-optimized DNA constructs that code for a codon optimized, (except for the FCS) 100% SARS-CoV-2 identical spike protein with an added trimerization domain were found in four (1, 2, 3, 4) patient samples collected in 2019, way before SARS-CoV-2 was first sequenced according to the official timeline. The samples were collected from a pneumonia patient with a pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. The sequences were found by a Spanish IT expert who had programmed an AI tool to screen the vast nucleotide databases for SARS-CoV-2 like sequences. The pcDNA plasmid also coded for several antibiotics resistances, and would not have been usable for a vaccine for humans. Unusually, in contrast to many vaccine designs, the spike transmembrane domain in the plasmids (which could destabilize the complex in absence of a viral membrane) was not replaced by a trimerization domain, the trimerization domain was simply added after the transmembrane domain.

As Steven Massey discovered, the multimerization domain in these plasmids is from a Chinese Harbin University patent, while the Foldon domain mentioned in DEFUSE was patented by the Scripps Insitute in the US. This is a difference, but there are many technical or financial reasons why they might have decided to try a slightly different domain from what was proposed.

But could there be any alternative explanations? We cannot completely exclude that these plasmids leaked into the samples during the later sequencing process. Many were working on SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in 2020. What speaks against that is that the plasmids found in the 2019 samples cannot be used in human vaccines due to plasmids that encode antibiotic resistances, and that experienced bioengineers would have likely removed the transmembrane domain. And although many SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were developed in China, none of them match these plasmids.

Again, the by far most plausible explanation seems to be that DEFUSE virologists did exactly what the planned to do. As the vaccine was meant for bats, they just used standard plasmids, and as they were not experienced in protein engineering, they failed to remove the transmembrane domain. Some of the mass-produced plasmids got into a human or into human samples, which were later sequenced, uploaded, and then found by the AI tool.

For over 20 years, coronaviruses have mostly been generated and manipulated in labs by assembling 5-8 DNA fragments encoding the viral genome in the correct order. This process requires the use of “sticky ends“—short, single-stranded DNA overhangs that serve as molecular magnets to link the fragments. These sticky ends must be unique and compatible at each junction. The complete DNA genome was then typically amplified using DNA constructs called bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) and transfected into Vero cells, as shown above in chapter 6.

The sticky ends were often generated by restriction enzymes that cut outside their recognition sites, allowing a few enzymes to produce many unique overhangs. Virologists initially used the less optimal enzyme BglI, which produces shorter sticky ends, but as bioengineering techniques evolved, more efficient type IIs enzymes like BsaI and BsmBI became standard tools and available as convenient kits for DNA assembly. DEFUSE virologists started using BsaI and BsmBI in 2017.

Type IIs enzymes cut adjacent to their recognition site, which enables two distinct cloning strategies. In traditional cloning, the recognition sequences remain in the final construct. In contrast, Golden Gate or “No See’m” cloning places the recognition sites outside of the cutting regions and sticky ends, so that the recognition sequences disappear in the final product. While Golden Gate cloning is simpler to design (allowing for uniform genome segmentation), it has a significant drawback: once the construct is complete, the absence of restriction sites prevents further modifications to specific regions. This can be likened to welding a radio into a car during production: it’s cost-effective if you’re sure of the best model, but if you plan to test different radios, using screws makes more sense—though initially more expensive, it allows easy swaps throughout the project. A similar strategy sometimes referred to as inward restriction site hierarchical cloning is frequently employed by experienced bioengineers.

DEFUSE virologists aimed to “screen 15-16 viruses to determine which strains to focus on… likely leaving them with 7-8” receptor-binding domains (RBDs). They also intended to test an undefined number of Furin cleavage sites (FCSs), “singly and in combination.” Even testing just two FCS variants alongside multiple RBDs would result in over 20 virus variants, far too many to justify assembling each full viral genome from scratch. Additionally, the DEFUSE proposal specified the use of “cDNA pieces linked by unique restriction endonuclease sites that do not disturb the coding sequence,” suggesting they employed a traditional restriction-site-based approach rather than Golden Gate cloning.

I am one of the authors of a preprint which argues that the SARS-CoV-2 genome displays a segmentation pattern (6 fragments under 8000 nucleotides each) for BsaI and BsmBI sites that is typical for lab-generated viruses (5-8 fragments under 8000 nucleotides each). This pattern is not present in closely related natural coronaviruses, and would require at least five mutations in these sites to match the pattern seen in SARS-CoV-2. The probability that natural coronavirus has such a pattern by chance was estimated to be around 1%. This was later confirmed when only 14 out of 1,316 beta coronaviruses were found to exhibit a similar segmentation pattern (for whatever reason, the author of that paper drew opposing conclusion from that finding).

Moreover, to easily modify the region including the RBD and FCS mentioned in DEFUSE, two restriction sites flanking these elements are necessary. In contrast to any other ~2700 known natural coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 is the only one whith a synthetic assembly fingerprint and exactly two BsaI sites flanking that region.

A year after we uploaded out preprint, draft documents of the DEFUSE proposal confirmed that DEFUSE virologists planned to use pretty much exactly the same viral genome assembly strategy that we had predicted. The draft references the purchase order number of BsmBI and states that they would “synthesize the genome using commercial vendors (e.g., BioBasic, etc.) as six contiguous cDNA pieces.” The predicted probability of finding a natural coronavirus with exactly six segments under 8000 nucleotides is approximately 1 in 4000, it has been observed in about 1 in 600 natural viruses.

The draft also mentions plans to generate a consensus genome of >95% identical SARS-related coronaviruses, which would explain why SARS-CoV-2 appears to have genetic elements from different viruses of various geographic regions, and why a direct ancestor has never been found.

The second and far more significant finding in our preprint was that, when SARS-CoV-2 is aligned to RaTG13, BsaI and BsmBI restriction sites contained about eight times more mutations compared to the rest of the genome. Would we expect to see this in lab-modified viruses? Yes, natural viruses typically do not show a required restriction site pattern, which is why DEFUSE virologists have selectively introduced silent mutations into these genome stitching sites in the past. And just very recently, a DEFUSE virologists published abother paper in which BsaI and BsmBI and the flanking method were used to assemble viral genome, and in which “Several silent mutations were included to disrupt naturally occurring restriction cleavage sites”.

But is there any natural explanation for these mutations? No. These DNA restriction sites only serve a function during genome assembly at the DNA level and are irrelevant in the virus’s RNA genome. The enzymes used are bacterial in origin and not found in any SARS-CoV-2 host organisms. Moreover, all mutations at these sites are silent, meaning they do not alter viral proteins and thus do not or only minimally affect viral fitness. These sites are scattered throughout the genome and do not correlate with known mutation hotspots. The preprint estimated the chance that such a concentration of mutations in these tiny recognition sites could arise through natural evolution to be less than one in a million. A recent reanalysis using more conservative parameters still found the probability to be less than one in 10,000.

One key argument against a laboratory origin is that many find it unimaginable that so many reputable scientists from so many different countries would lie when saying that SARS-CoV-2 is certainly or almost certainly of natural origin.

I have always viewed scientists as the most reliable source of information on disputed topics. Many of them enjoy the protection of tenure, which should allow them to speak inconvenient truths without serious financial consequences. While occasional “bad apples” are to be expected in every field, could so many professors from Western societies knowingly publish the opposite of what they believe in the most prestigious scientific journals? I would have thought that impossible.

However, a more scientific look at this issue paints a different picture. History offers many examples of established scientists fiercely resisting the truth when it threatened their reputations or core beliefs. Prominent examples include Galileo Galilei, Ignaz Semmelweis, Albert Einstein, and others.

When we look at how individuals behave when their organizations or peer groups cause serious harm, the situation is similarly grim. Consider recent cases like child abuse in the Catholic Church or the use of cheat devices to manipulate car emissions, both of which likely harmed millions of people in different ways. Among hundreds, possibly thousands, of people involved in these scandals, how many put the victims or societal interests above their own? How many exposed what was happening to prevent further harm? None. Everyone either stayed silent or actively misled the public.

Scientists are not all independent either. The NIH directly funded “gain-of-function” research on coronaviruses at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China. Most US scientists rely on NIH grants, have Chinese lab members, or collaborate with Chinese scientists. At a SARS-CoV-2 origin Senate hearing, high-level NIH officials were found to have evaded transparency, deleted government records, and lied. Speaking out became dangerous, and those who did so on other topics faced vicious media attacks. What about virologists in Europe? The EU also funded gain-of-function research, as well as research at the WIV. Dutch virologists collaborated directly with Peter Daszak’s EcoHealth Alliance. Germany funded a Sino-German Transregional Collaborative Research Center with Wuhan University and the WIV, as well as a project involving respiratory viruses, gain-of-function research, and proteolytic activation which could mean inserting a Furin cleavage site. Not only virologists, but government officials too, could have strong motives to cover up these activities.

Without evidence proving that virologists behave more ethically than priests or engineers, we should thus expect most virologists to either stay silent or mislead the public to protect their reputations and peer group if SARS-CoV-2 were a manipulated virus.

But how ethical did virologists actually behave during the debate on the origins of SARS-CoV-2? When the WHO sent Peter Daszak, principal investigator of the DEFUSE project, to Wuhan to investigate the virus’s origin, he had more than obvious conflicts of interest, given his role as a funder and long-term collaborator with the Wuhan Institute of Virology. How many virologists do you remember that warned the public about these conflicts of interest?

Or let’s consider the fact that, relatively to its population, Wuhan was the Chinese city conducting the most SARS-related coronavirus experiments. When a European virologist was asked by the German Robert Koch Institute if he would rule out a lab escape theory for SARS-CoV-2, he responded, “I would certainly discard the thesis that SARS-CoV-2 was created in a lab. I also do not think that it escaped from a lab. From what I know, the Wuhan lab was not working with live SARS viruses. Research with SARS-CoV was not allowed in China because of a lab accident in 2004. They became cautious about permitting experiments with such viruses.”

What about the inserted Furin cleavage site? For about a year, thousands of scientists puzzled over how this virus acquired a cleanly inserted Furin cleavage site in its spike protein. How many of the virologists involved in the DEFUSE proposal informed the public that they had considered engineering exactly such a site into bat coronaviruses? Not one. The proposal was leaked by DARPA employee Major Murphy and D.R.A.S.T.I.C. network member Mr. Rixey. When it was leaked, it mentioned the Furin cleavage site and the insertion of protease cleavage sites at the S1/S2 interface. It took another FOIA lawsuit to obtain the drafts, which explicitly mentioned inserting a Furin cleavage site at the S1/S2 interface.

As for biosafety, in the DEFUSE drafts, Daszak wrote, “The BSL2 nature of work on SARS-related coronaviruses makes our system highly cost-effective.” True – research costs are reduced when even simple face masks aren’t mandated for such experiments. One scientist noted, “In China, they might be growing these viruses under BSL2,” though US reviewers of the grant application “will likely freak out.” In the documents, the “2” in BSL2 was then simply replaced with a “3”, and Daszak commented, “Once we get the funds, we can allocate who does what exact work, and I believe a lot of these assays can be done in Wuhan.”

What about the restriction sites? When virologists wrote a press release about our preprint, they simply omitted the most significant finding: the high frequency of mutations in these sites. The publication of the preprint was later suppressed.

Regarding misleading publications about the origins of SARS-CoV-2, an early statement in The Lancet that “strongly condemned conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin” was coordinated by Peter Daszak. The most-cited paper on the topic, Proximal Origin, concluded that “SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.” Yet, in private chats, the authors said an “accidental escape is in fact highly likely” and admitted, “I really can’t think of a plausible natural scenario where you get from the bat virus… to nCoV where you insert exactly 4 amino acids (12 nucleotides) that all have to be added at the exact same time… and you don’t change any other amino acid in S2? I just can’t figure out how this gets accomplished in nature.” A colleague commented, “If we assume passaging (in a lab) as a possible scenario here, we must assume it is also plausible for all outbreaks from the past…” They agreed to focus on other scenarios to “limit the chance of new biosafety discussions that would unnecessarily obstruct future attempts of virus culturing.” When a New York Times reporter asked how they could rule out the possibility that Wuhan scientists accidentally released a natural virus, they remarked, “Every reporter can be misled.”

The most cited paper on the topic, proximal origin, concluded that “SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus”. In private chats, the authors said “accidental escape is in fact highly likely” and “I really can’t think of a plausible natural scenario where you get from the bat virus or one very similar to it to nCoV (which is what SARS-CoV-2 was called back then) where you insert exactly 4 amino acids 12 nucleotide that all have to be added at the exact same time to gain this function – that and you don’t change any other amino acid in S2? I just can’t figure out how this gets accomplished in nature.” Their colleague commented “If we assume passaging (in a lab) as a possible scenario here, we must assume it is also plausible for all outbreaks from the past…” and that the manuscript should focus on other scenarios to “limit the chance of new biosafety discussions that would unnecessarily obstruct future attempts of virus culturing”. When a New York Times reporter asked how they could exclude the possibility that Wuhan scientists had accidentally released a non-manipulated natural virus, they commented “spot on, better don’t tell him” and “every reporter can be misled”.

This brings us to the issue of science “journalism.” Much of the evidence discussed in this article contradicts what is frequently reported in major newspapers. One might expect that a global crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic would have prompted an intense response from science journalists – collaborating on investigative projects, suing universities and funding agencies for access to internal communications, and doing everything possible to uncover the origins of the virus.

While some journalists and small nonprofit organizations in the U.S. have made very valuable contributions in investigating the origins of SARS-CoV-2, the majority of large media outlets – both in the U.S. and Europe – seem to continue to treat the subject the same way they cover routine scientific discoveries, such as the identification of a new species. Typically, a reporter identifies an interesting study, interviews the scientist involved, simplifies the material for the public, and publishes an article – often within a single day. Fact-checking or scrutinizing the claims would take too much time, so most science communicators rely on quotes and trust the peer-review process. This “copy-paste” approach makes them more like SciCom zombies (“Scombies”) – simply transcribing what scientists say without questioning or verifying anything.

Challenging those in authority is rare in science journalism, much like how the Catholic Church’s authority went unchallenged when it came to child abuse for so long. Reporters may fear losing access to sources or damaging relationships with well-connected scientists. Sadly, the cartoon isn’t a satirical exaggeration – virologists conducted risky experiments without mandating even basic protective measures like masks, and they explicitly said that every reporter can be misled. I have given many interviews which were never printed. The reason was never that anything I had said was wrong. The reasons were “the editor didn’t like the interview” or that the “journalist” “wanted to reach out to virologists”. Recent examples of Scombie writing include highly misleading articles about SARS-CoV-2 nucleotides found at the Wuhan Seafood Market.

The evidence is clear. SARS-CoV-2 was manipulated in a lab. This is also confiremd by statistical analyses that cover about two-thirds of the point I mention. A laboratory origin of SARS-CoV-2 is proven beyond reasonable doubt.

Here’s what must have happened: Some DEFUSE virologists or close collaborators followed through on ideas from that project. As few as one or two scientists could have carried out the virus engineering described in DEFUSE. They ordered the mentioned six DNA segments, costing roughly $6,000, assembled them maybe within a week, and, underestimating the virus’s infectivity, inadvertently infected themselves. The RBD that they had picked based on predicted binding to the human ACE2 receptor made the virus uncontainable. The FCS enabled it to infect neurons and to cause severe harm in vulnerable populations, claiming 28 million lives. They had generated exactly the unpredictable, artificial risk that other scientists had warned about.

Similar to how the Soviet Union tried to cover up the Chernobyl disaster, the Chinese Communist Party sought to obscure the origins of SARS-CoV-2. And like many organizations implicated in major scandals, the international virological community also fell in line, failing to admit their own wrong risk assessments and to point out their colleagues’ catastrophic negligence with regards to biosafety. I don’t think they were necessarily lying – it’s more likely that they couldn’t emotionally or intellectually process the fact that the research they advocated for in the US and Europe was now causing the deaths thousands of so many patients treated in their own institutions.

The pandemic started around 5 years ago. And although some countries, like the U.S., have begun revising oversight regulations for this type of research, the majority of nations have yet to initiate impartial investigations or make at least the most dangerous experiments illegal.

It looks like this issue will just be ignored for now, just like the Catholic Church’s handling of abuse cases was ignored for decades. Discussing such topics is incredibly difficult, reaching a consensus that everyone agrees to may be impossible. Assuming that scientists would just objectively and openly discuss if some of them had caused more casualties than World War I is insanely naïve. Many in the scientific community tried to silence, insult and character assassinate those who raised this topic, even highly reputable scientists with dissenting voices are now excluded from conferences.

As we have seen with Ignaz Semmelweis, many lives can be saved by implementing very simple solutions such as washing hands before delivering a child. Similarly, another pandemic of an unstoppable lab-modified pathogen could be prevented by just banning experiments that plausibly increase the infectivity or lethality of human pathogens. This would only affect a tiny fraction of the biomedical community. These highly trained researchers could easily find jobs related fields. And we would even have a template for a successful international organization that could supervise that such an international ban is adhered to: the IAEA.

However, just like with Semmelweis, such change requires that people with lots of authority admit that they had made a terrible mistake or are forced to change their behaviour. This did not happen during the last four years, and I do not see why it should spontaneously happen any time soon. Just like with the Catholic Church, the consequences of this inaction could be terrible. For instance, the lack of expected mutations in the virus responsible for the 2021 Ebola outbreak strongly suggest that it was either generated in a lab or had been frozen in a lab for five years. And virologists are also tinkering with viruses up to 100-fold more deadly than SARS-CoV-2.

I deeply regret not having had the foresight to realize how dangerous my colleagues’ experiments were sooner and thus failing to try to prevent them. I have since written many articles, gave academic talks and interviews (German and English), and contacted numerous politicians. While I heard that these were read by very influential people in the US, I did not achieve anything in Germany and most other countries that still fund Gain of Function experiments. The only way I see to prevent the next pandemic is to ask for YOUR help.

PLEASE do something.

Even if you don’t feel equipped to evaluate the evidence presented here, anyone can ask for an impartial investigation into the origins of SARS-CoV-2. Please urge your representative to act, and tell them that you will not vote for any party that looks the other way when millions of people die. Write an email, or better a letter, such as this.

If you encounter superficial or misleading “Scombie” journalism on the origin of SARS-CoV-2, cancel your subscription or block that source from your news feed. And write an email to the editor-in-chief to let them know why you did so!

Or, if you can, support nonprofit organizations like US Right To Know or BiosafetyNow, which focus on this crucial issue.

Together, we can prevent the next lab-derived pandemic.

THANK YOU!

some figures generated with biorender.com