“Trumpism,” our issue focusing on the global right, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition at a discounted rate today.

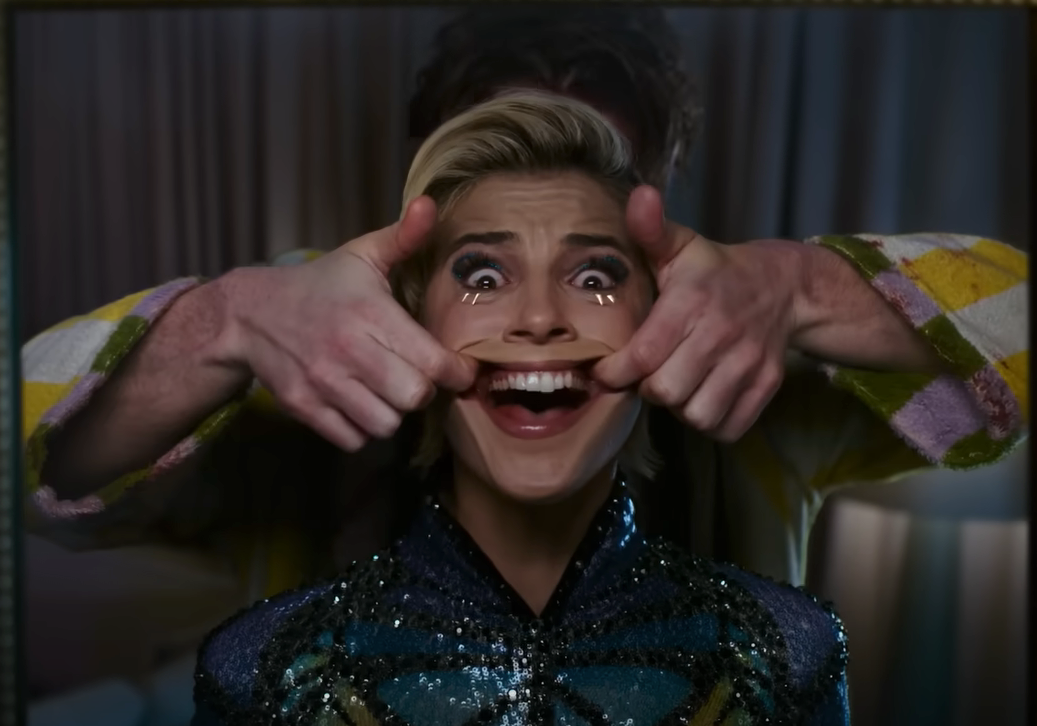

No one in Smile or its sequel, Smile 2, has figured out how to beat the monster. This is a skinless, meaty, human-ish parasite in search of hosts. It drives its victims to suicide by stalking them with hallucinated images. If you see someone die in this way, you are next. You will begin to see something that “looks like people but is not a person,” as a distressed student puts it in the first film. Such people have their faces pulled into the titular rictus.

In Smile, the monster resembles the pressure incumbent upon us all, no matter how traumatized, to put on a smile for the world. The sequel adds something new. Here the smile infects a commodity: a pop star, Skye Riley, played by Naomi Scott. A smile is already being forced out of Skye by a rival monstrosity: her record company. Exposure to the smile monster only compounds the pressure.

Smile 2 shows a horrifying scenario in which the urge to do violence to the body presents itself as the only way to fight back against the self-destroying demands of capital. It is a film about life in a system that values people solely for their ability to perform profitable functions and demands good cheer in the face of relentless exploitation. Yet despite its realism, the film is framed by a fictional premise: the idea that there is no way out other than self-destruction.

Shaping Smile 2 is a tension between person and brand. Everyone in Skye’s life is more interested in the latter: her momager Elizabeth (Rosemarie DeWitt), her assistant Joshua (Miles Gutierrez-Riley), Darius, the head of her record company (Raúl Castillo), a high school acquaintance turned drug dealer (Lukas Gage), even Drew Barrymore (playing herself). Her team wants her to stay hydrated, keep to her sleep schedule, and show up at rehearsals. Her toxic fandom wants the Skye Riley of their parasocial dreams.

In Smile 2, the alienation, inauthenticity, and human disposability is the point.

After work, she retreats to an apartment straight out of an Architectural Digest video tour. The dark wallpaper with bold accents and animal-print fabrics offer no happiness. This is a place to recharge for tomorrow. Skye might as well be the electric toothbrush she clings to in one scene.

Skye is preparing for her comeback tour. A year earlier she was in a drug-fueled car crash that killed her celebrity boyfriend Paul Hudson (played by the son of real-life celebrity Jack Nicholson, whose creepy smile in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is the obvious prototype for the film’s telltale symptom). Skye’s struggle with sobriety leads to her exposure to the smile. Desperate for relief from pain, she turns to a Vicodin-selling dealer — but he, accidentally caught up in the murder of his suppliers, has started to see the smile.

There is a muscular choreography to character relations in Smile 2, sometimes literally. Skye’s estrangement is most acute in scenes with her backup dancers. These people delicately handle her body. They become one with her in a rhythmic assemblage on stage and in the studio. But when she trips up, all they can do is stand at a distance, asking if she is OK. The awkwardness is so intense, born from a depiction of the intimacy workers end up having with bosses and company assets, even coworkers. It is a fragile kind of intimacy that can revert to stark unfamiliarity at any moment. In Smile 2, solidarity is an illusion.

Skye instead looks for comfort in her own music. For us, too, this music serves as a welcome break from otherwise nerve-scratching audio. Little moments of song are reminiscent of M. Night Shyamalan’s Trap (2024) in that they promise safety in a bankable, immersive experience. But it is during one of these, in a dress rehearsal, when Ray Nicholson pops out with his creepy IP smile, looking like a digitally de-aged version of his real-life father.

It occurred to me that there’s something sad about an actor being cast simply because their smile is really the smile from a different movie. But that alienation, inauthenticity, and human disposability is the point.

The other salient feature of Smile 2 is that it dials the body horror up to eleven. The opening sequence ends panning over a disembodied foot and blood smeared into snow and tarmac. Skye pukes after seeing Lewis the drug dealer bash his own head in with an Olympic weight plate. Thud after thud, skin slouches thickly and blood drips and burps from the piggish meat of his face. This scene introduces a sort of squelching flesh noise that is the first thing to haunt Skye. Elsewhere eyeballs are ripped out, red seeps in between the gaps of teeth, bones jut out of legs, and mouths are gaped beyond rupture. Eventually the smile monster discards its human skins, freeing a toothy jaw and stretching out like a floating carcass.

The body is something to be managed in Smile 2, and the smile monster assaults its victims with the implications of this management. Skye has internalized various techniques of bodily care, not least an impressive habit of chugging Voss water to deal with cravings or general anxiety. The record label has conscripted the maternal forces of Elizabeth and Joshua into making sure that Skye does not have any more life-threatening accidents. She needs to stay alive to be profitable. Skye’s ride-or-die bestie Gemma (Dylan Gelula) returns to feed her matcha, drive the car, and keep this investment calm at night. Sobriety for Skye means using drugs not for fun but to assuage the pain that makes her dancing clunky and threatens performance.

Smile 2 offers a view of neoliberal biopolitics in spectacular microcosm. The record label has a stake in ensuring that Skye retains the bare minimum of life and physical appearance needed to sell tickets. It has no interest in guaranteeing quality of life beyond this requirement. It would prefer if Skye were alienated from anyone who would distract her from routine. At one point, Skye must escape from a wellness clinic called Harvest Moon, where she has been confined for a single pressurized day of rest before the tour resumes.

The smile monster is an extension of the logic already plaguing Skye Riley. Like her own mother, it wants to force its thumbs into her mouth and push up the corners. It wants to make people smile without giving them a reason to smile. It wants to make a smile that is only a contraction of nerves, merely a guarantee that a subject is alive. It makes people think that this sort of extractive, transactional interest is the only kind any person can have in another’s happiness.

Under these conditions, Skye, like everyone afflicted with the smile, pursues the only path of liberation that seems to be available: brutal self-harm. Skye already copes with the pressure of her role by pulling out chunks of her hair. For as much as she feels herself in her music and dancing, she longs to be rid of this self that, properly speaking, belongs to investors. Exposure to the smile monster exacerbates this morbid urge tenfold.

Both Smile films follow the intensifying urge to do life-ending harm to the body when it is manipulated and forced to endure a bare life of smiling for no reason. The smile monster preys on its victims by persuading them they are no more than merely alive. The suicides in these movies happen in two stages: First, victims are taunted with the alienation they experience from any part of themselves beyond mere biological life. Second, the death impulse threatens to end biological life itself.

We are all vulnerable to internalizing the message that comes from centers of power: we do not care about how you live, only that you live.

In a paradoxical act of resilient self-defense, victims turn on themselves. They grab sharp and heavy objects and destroy the flesh, believing without exception that they are depriving the smile monster of the only thing that matters to it — the fleshly medium of expression for the smile itself.

The true horror of Smile 2 is that its protagonist accepts the terms with which her life has been constrained.

I will not spoil the ending of the film. But I would not be writing if I thought we should follow Skye’s lead. It is not hard to find examples today of people viewing biological life as the only thing of value. From the standpoint of employers and the neoliberalized state, what matters is that we are alive and able to perform sanctioned social functions — not that we are fulfilled or self-actualized.

We are all vulnerable to internalizing the message that comes from centers of power: we do not care about how you live, only that you live. Moreover, this message is muddied by the fact that, under certain circumstances (citizenship status, reproductive status, ethnicity, and so on), survival is not a concern, revealed in a rising indifference to the continued existence of a growing number of people.

For many people, it can be hard to see an alternative beyond self-destruction — a fact reflected in the startling incidence of drug addiction, suicide, and deaths of despair. When people are tasked with recharging the device of their bodies at home and powering on again each morning for another round of soulless exploitation, there is an understandable allure to sabotaging the machinery itself.

The provocation of Smile 2, itself a property of Paramount Pictures and others, is that the film finds power only in self-destruction, seemingly unable to imagine another option. There are scenes where Skye tries hard to envision the absence of the smile monster. She fails. Smile 2 longs for a supplemental remedy.

But however resonant the analogy, we are not like the victims of the smile monster. We do not have to accept the idea that we are vessels for profitability, that our basic survival and functionality are all we’re good for. We can imagine an alternative that the film can’t: the collective, political assertion of social life and subjectivity in a world intent on denying them.

Elliott Piros teaches Greek and Roman history and Latin at universities in the Los Angeles area.